...your product has striven to succeed and may even have enjoyed a long life—or perhaps not—but in any case, the Scrum Team has achieved the Vision or its relevance is past, or it becomes obvious that the product will not achieve its Vision, or people agree that the Vision is so misplaced as not to further pursue it.

✥ ✥ ✥

Killing off products is often what organizations are worst at. Few living things are immortal, and the cycles of nature ultimately bring great works back to the dust from which they arose.

People become invested in their creations, almost as if they were their children, born out of love and noble aspirations. This happens at the level of individual visionaries (like Product Owners) but also at the level of entire enterprises or communities (like the Saturn automobile, or the Philadelphia Giants, or Nokia, or the Lisp programming language). It’s always possible to put enough energy into a system to fight entropy, but at some point, the energy and cost expended aren’t worth the limited harmony that the product contributes to the environment.

You’d like products to last forever, but growth leads to clutter, and humanity learns in jumps and stages that usually leave the creations of human endeavor obsolete. You could perpetuate them into the future but the benefit and utility sometimes don’t cover the pain and effort to sustain them.

And endings can be painful. To end a product is to bring an end to the livelihood of many. The demise of a product can leave the bereaved in a state of denial, and closure comes hard. Yet to heroically strive to keep the product afloat is usually futile and results in repeated increments of layoffs and death by a thousand cuts.

Often, when Value Areas diversify within a product or as the result of a Value Stream Fork, a product’s demise might give rise to its own successor. Even though the product may disappear along with its old identity, the market need may persist.

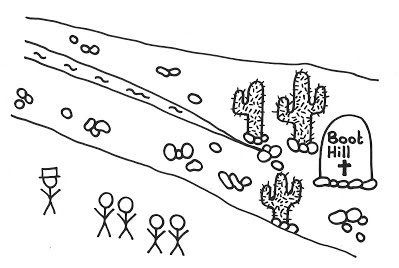

Therefore:At the end of its life, give a product a decent burial. Bring development efforts to closure with finality and dignity. Keep everything transparent so that the demise unfolds in line with stakeholders’ expectations. Create a transition of good grief.

Hold a retrospective to reflect on the product’s place in history and to archive key learnings. One wonders if NeXT (a company founded by Steve Jobs in 1985) consciously archived the technology that would pop up in Apple a few months later. If there are bright spots in the product’s history worth celebrating, by all means celebrate them.

✥ ✥ ✥

Scrum doesn’t say when to kill a product’s development, but it does tell us that the Product Owner is accountable for value. The Product Owner should be the final decision point, though the need here is strong for as broad a consensus as possible. ROI is one consideration. And timing is everything: it’s good to kill a product before it ends a slide into negative value from which there is no return. Data, forecasts, and analytics can help, but it is not easy to dismiss the valid place of feeling and experience in these decisions.

Google in particular has been good at killing off low-value lines of business, such as Google Video, Google Desktop, Wave—no fewer than thirty-seven products at this writing. This is not to say that they maintain only a nose-to-the-grindstone, near-term profitability focus—they continue to explore self-driving cars, energy-producing kites, and a host of other high-risk ventures.

Death isn’t always about killing: in the norm, it’s an everyday part of life. Sometimes what were once good products simply come to the end of their useful life. Customized software to support a town festival is retired after the festival is over. Such ends-of-the-road are particularly worth celebrating and reflecting upon.

Try to bring finality to the demise. Be done and move on. This pattern is named for the ceremony that the team might hold to bring the demise to closure, and such a ceremony can help a team and its people move on. Look for opportunities to apply the talent in new or existing products—both the Product Owner and ScrumMaster have responsibilities here, to support the individuals on the team and help them to their transition to a new station in life.

That a product comes to its end doesn’t necessarily imply that its Scrum Team will split up. Teams often stick together across product developments within a corporation and sometimes across companies. See Stable Teams.

Money for Nothing has much in common with this pattern, because it might bring development to a “premature” end in light of optimizing overall value. See also Failed Project Wake.

Picture credits: Shutterstock.com.