Every Monday morning the CEO of our 5000 person company would send out an email starting with the words “Hello Team.” We all knew we were not One Team.

...complex product development is a collaborative activity that requires people working together to build it. When people are working together with a common goal, having these people work as a team is usually the best way to optimize the work.

There is an emerging Product Vision and energy to pursue it is gathering as the stakeholders come out of The Mist.

✥ ✥ ✥

When there’s a ton of work ahead, you are tempted to throw the world at it. But complex work demands a high degree of shared knowledge and coordination, such as product design and development. This kind of work defies such an approach.

There are clear advantages to having more than one person carry out difficult work. With many eyes and voices, the team can avoid the biases that might arise in solo efforts. And everyone learns firsthand from exploring the new frontiers that a team encounters during complex development. This can lead to large groups of people trying to work together. Such teams tend to attract specialists and that tends to make the team grow.

Deadlines may push you to allocate as many people as you can to work in parallel to get it done. But unless the work is decomposable into independent parts, any time savings will be more than eaten up by communication and coordination overhead.

When status within an organization is proportional to team size, large teams can emerge as a part of the politics of the organization.

Having large teams of people working together means having fewer small teams. It is tempting to think that having large teams reduces the hassles of having numerous small teams. But there is no such thing as a large team. Large organizations self-organize into small (sub-)teams that can get things done. You may think having one big team is going to be easy, but then you end up with a heap of smaller ones anyway. So why not start with what works and the structure to which groups of people naturally evolve?

Having a large group of people working together on interdependent tasks unfortunately leads to unexpected problems.

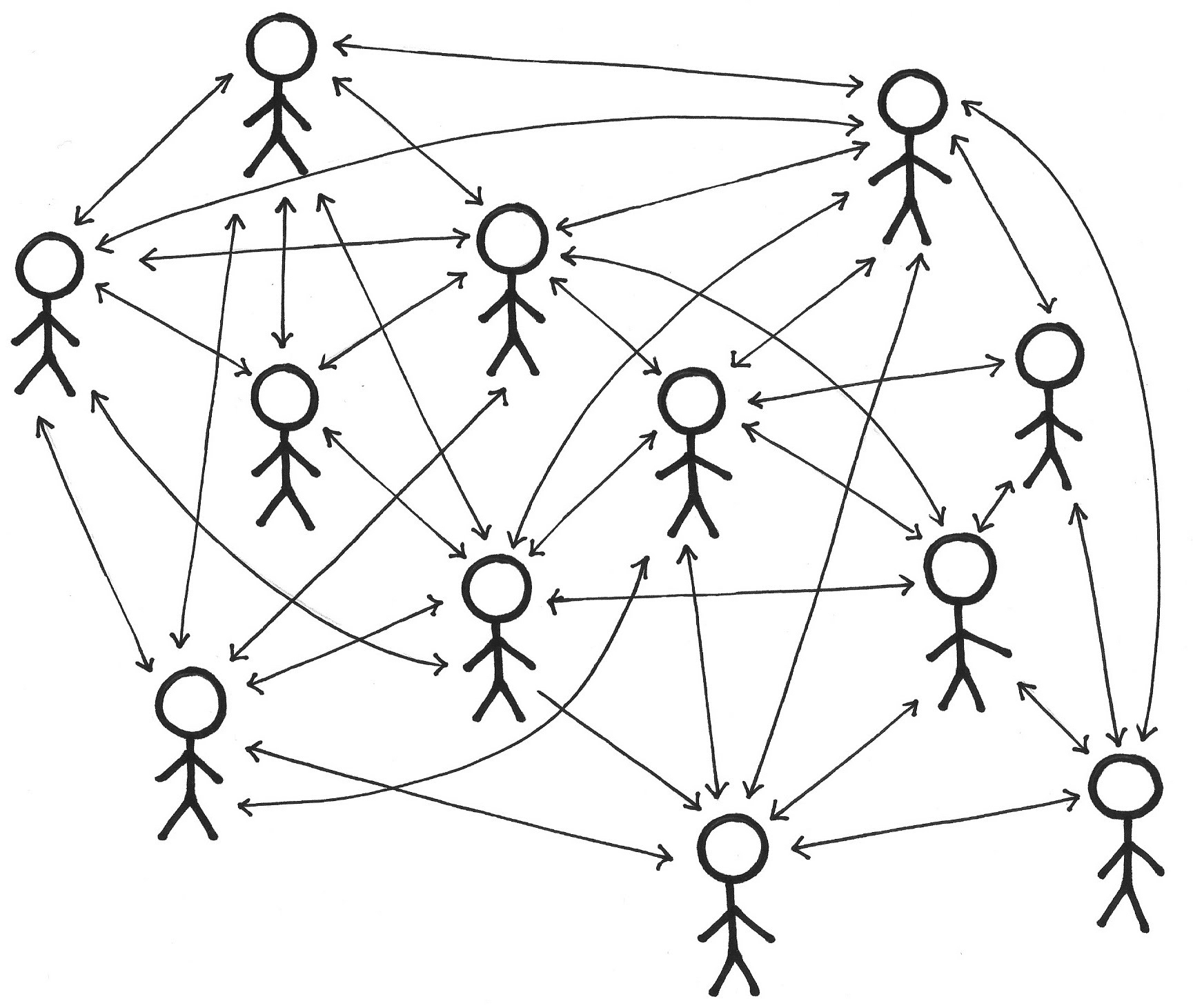

The more people working together, the greater the overhead of communication. Good communication is essential for effective teamwork; however, this overhead has a harmful effect on communication quality. As the group grows, there is proportionally less information transferred within the group, yet there needs to be more information transferred with the increased number of people. Taken to extreme, communication and coordination overhead consumes nearly all the resources of the group, leaving almost no time to do productive work. This is like the problem in computers called “thrashing” where a lot of energy is expended without actually accomplishing anything. Alternatively, the organization may designate communication clearinghouses such as management roles, decision forums, and committees that are organizational structures in their own right. These extra communication links create communication bottlenecks, impair communication fidelity, or both.

With larger groups of people, the relative contribution of everyone diminishes. This can have a non-negligible motivational effect, as free riding and social loafing (where the individuals contribute less in the group than they would working on their own) increases as the size of the team increases. The result can be that large groups produce less than small groups, or that large groups produce lower-quality outcomes than small groups.

When there are large groups of people working together, there is a greater need to coordinate these individuals. This coordination effort is called process loss. As Steiner described in 1972, the actual productivity of a team is the potential productivity minus the process loss ([2]). As team size increases so does the process loss, effectively limiting the growth of productivity with increasing team size. In these situations, teams add more and more roles to support coordination that do not add value and effectively reduce the productivity of the team (the number of roles like this in a team is the Wally Number, named after Scott Adam’s character in Dilbert).

Christopher Alexander cites a study that shows communication effectiveness drops with an increase in group size. In his pattern, “Small Meeting Rooms,” he notes that during meetings, “[i]n a group of 12, one person never talks. In a group of 24, there are 6 people who never talk” (“Small Meeting Rooms” in [1], pattern 151).

Despite the conjecturally legitimate forces that lead to having larger teams, these large groups of people come with significant problems.

Therefore:

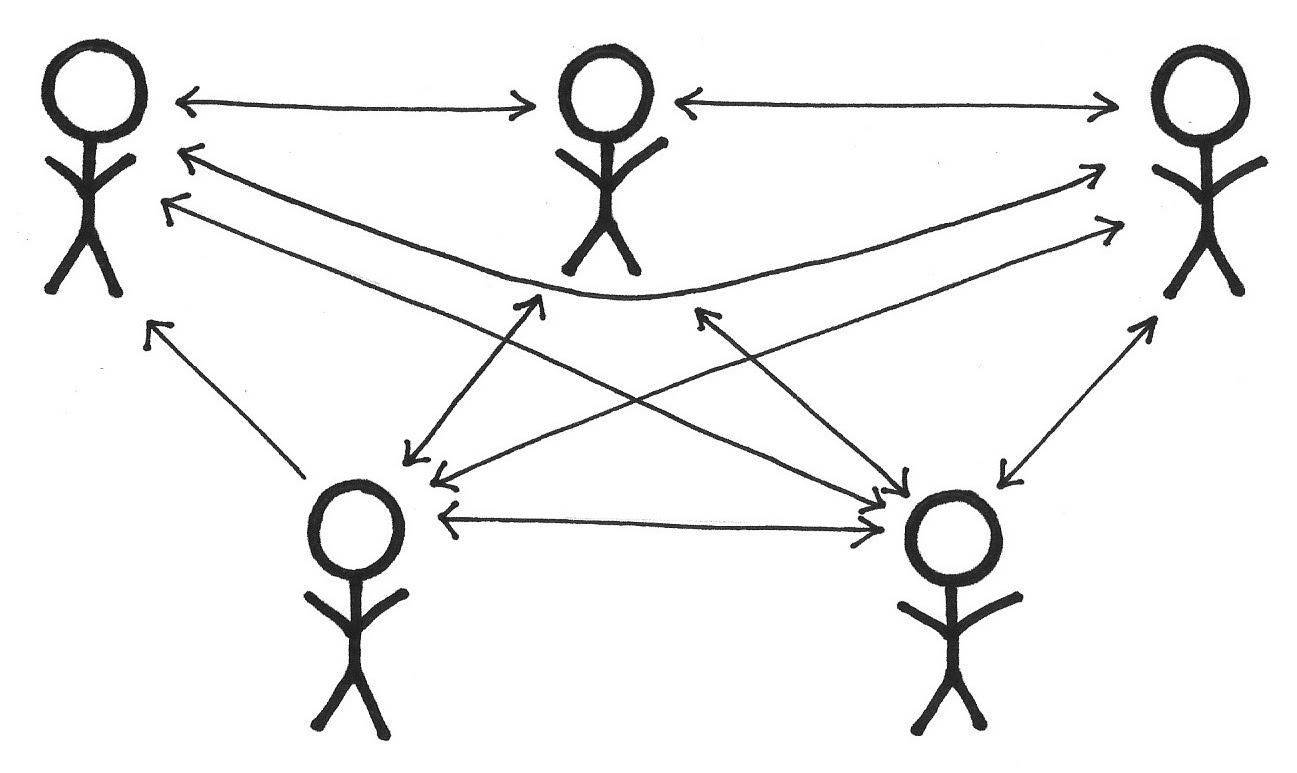

Use Small Teams of people working on serialized work rather than striving for false parallelism.

Consider Scrum Teams to be around five or so people. They need the appropriate expertise and the ability to work together, which can lead to a Cross-Functional Team.

People working in Small Teams have a greater sense of attachment to the team and the goals of the team, have better communication within the team with more opportunities to be heard, and are generally more productive. Small Teams help overcome negative teamwork effects such as social loafing and process loss as well as facilitate more positive effects like the Kohler effect (motivation to not be the worst-performing member of a team).

✥ ✥ ✥

In a Small, Cross-Functional Team, it may be challenging to work out who needs to be on the team to create the Product Increment. Rather than incurring the overhead of an oracle (such as a manager) or other additional role to work this out, try using Self-Selecting Teams. Where the team size starts to grow, an opportunity exists for exploring more deeply the organizational problems for which growth tries to compensate. For example, an overly complex architecture may lead to a team that depends on many specialists working together to complete the increment. It is a good investment to resolve these issues by striving to keep the team small while still being able to deliver a product increment. Both the product and process can benefit from such tidiness.

Broad research efforts have shown small teams to be more effective than larger teams in many dimensions, and that people prefer being in small teams to being in a larger organization. In 1958, participants in research by Slater preferred being in a team of five rather than larger teams ([2], p. 86). The team members found that larger teams were less coordinated, more difficult to share ideas in, and were not as effective in using the team member’s time. Members of smaller teams (two to four members) also preferred to be in teams of five, showing a preference for small team size. Research conducted by Kameda et al. in 1992 shows increasing performance with larger team size, then decreasing performance above a certain point. The experiment used team sizes of two, four, six, and twelve people. The conclusion was that the performance of members in a team of four people was highest ([3]). In more recent research on software development, teams with nine or more people were found to be less productive than teams with fewer than nine members ([4]). Other studies have shown that a critical mass of three people was both necessary and sufficient to perform better than the best individuals. So, though small is beautiful, three is probably a lower bound on effective team size ([5]).

Experiment to find the best size for your team: we will not give you an optimal number here. Most efforts start with one or two people and then grow when they receive official funding. Remember that great teams grow from small teams that work. Add new team members with great trepidation. Cross-training and broadening expertise across the team is almost always better in the long term than growing the team to compensate for missing expertise. Cutting people from an overly large team to achieve the right size can lead people to grieve over the broken relationship. It is better to look for natural opportunities to move people out of the group such as attrition, promotion, or a team member’s initiative to seek career opportunities in another team.

Larger teams (statistically) experience more churn than smaller teams, so the larger a team is, the less likely it is that its membership will be stable over time. Small Teams therefore support Stable Teams.

If a team starts to grow too large, consider Mitosis.

[1] Christopher Alexander et al. “Small Meeting Rooms.” In A Pattern Language. Oxford University Press, 1977, pattern 151, p. 713.

[2] Ivan Dale Steiner. Group Process and Productivity. New York: Academic Press, 1972, p. 86.

[3] Tatsuya Kameda, Mark F. Stasson, James H. Davis, Craig D. Parks and Suzi K. Zimmerman. “Social Dilemmas, Subgroups, and Motivation Loss in Task-Oriented Groups: In Search of an ‘Optimal’ Team Size in Division of Work.” In Social Psychology Quarterly 55(1), Mar. 1992, pp. 47-56.

[4] Daniel Rodríguez, Miguel-Ángel Sicilia, Elena García Barriocanal, and Rachel Harrison. “Empirical findings on team size and productivity in software development.” In Journal of Systems and Software 85(3), March 2012, pp. 562-570.

[5] Patrick R. Laughlin, Erin C. Hatch, Jonathan S. Silver, and Lee Boh. “Groups Perform Better Than the Best Individuals on Letters-to-Numbers Problems: Effects of Group Size.” In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90(4), 2006, pp. 644-651.

Picture credits: The Scrum Patterns Group (Lachlan Heasman).