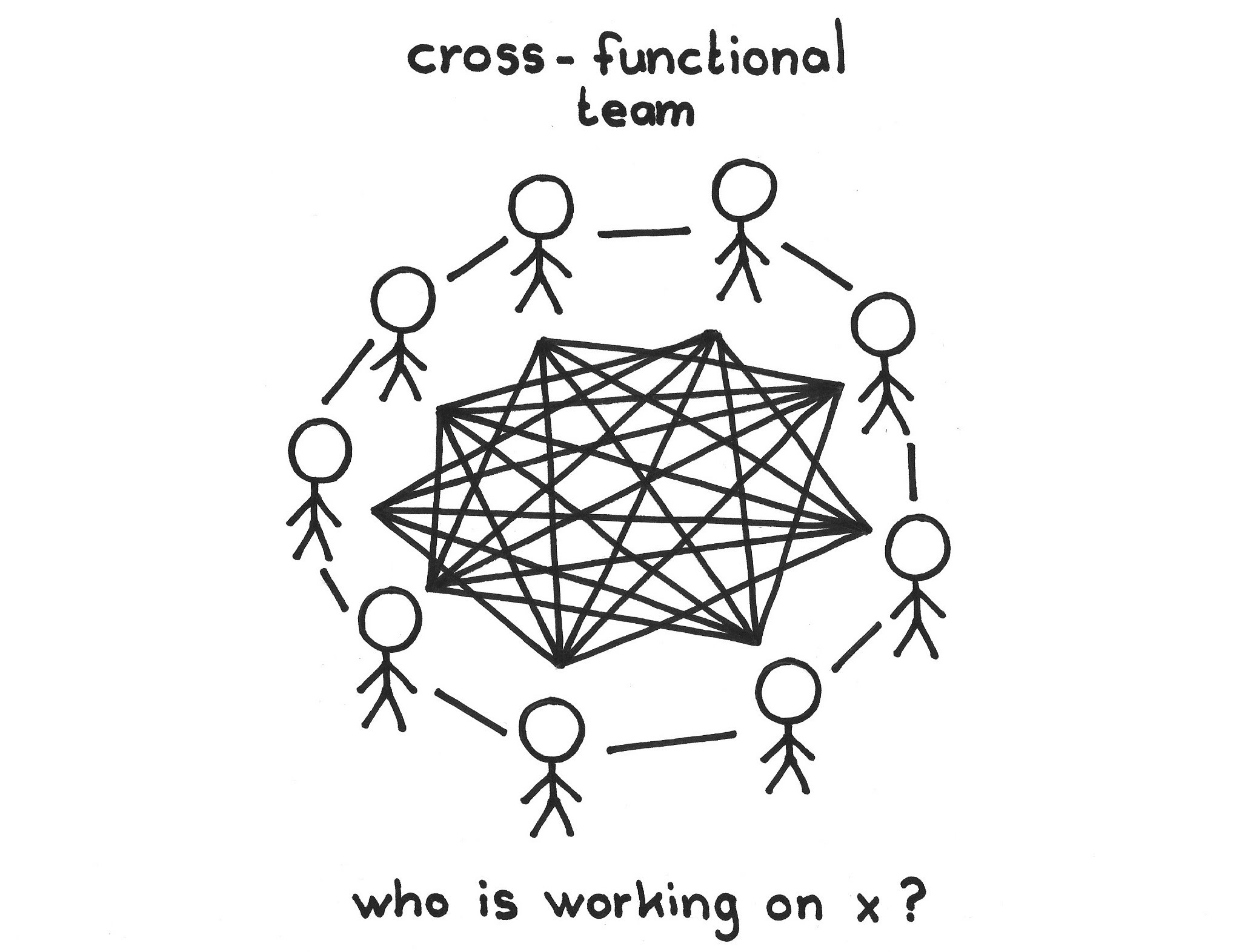

…you’ve been adding people to the team to keep up with stakeholder demand. However, the team is starting to work more as two teams than one, and team members have difficulty tracking everything that’s going on.

✥ ✥ ✥

One should grow a Scrum Team in an incremental, piecemeal fashion, but eventually the team just becomes too large to remain efficient. Small Teams are the most efficient, but sometimes you need to grow. You could grow the organization large enough to be able to meet market demands for an increased breadth or volume of features, but large teams tend to be inefficient. Fred Brooks said that two programmers can do in two months what one programmer can do in one month (as in [1]): one realizes little benefit by adding more people to an existing development effort. Adding team members incrementally smooths out the “ramp-up cost” of transition but results in a crowd rather than a team.

One team for one product is the most efficient way to work. All team members will know exactly how their work fits into the past, present, and future. They can change direction quickly if the work of other team members requires it. The learning you get from working flows more naturally in one team than in two. It is easier for the Product Owner to coordinate with one Development Team than with two. Handling two teams creates more work for the ScrumMaster; having a ScrumMaster per team adds another line of coordination.

We can distinguish between the terms formal team and instrumental team. A formal team is what you see on the org chart, and corresponds to titled positions like ScrumMaster and Product Owner. However, instrumental teams come from the empirical loci of social interactions between individuals. It is a good thing to align the informal and formal structures. And while it’s also good to have one team as described earlier, it’s folly to pretend that two empirical teams are in fact one team.

You could hire a new team on the side, but the effort to bring a group of new people up to speed on the product, culture, and technology is awkward. As a rule of thumb, every person you add to a product development organization detracts 25 percent from the effectiveness of everyone in that organization for about six months. In any case, there is “ramp-up” time associated with each new staff member, and that time and its corresponding overhead grow larger as the organization grows larger (Brooks’ Law [2]). Furthermore, you need substantial cash on hand or a strong cash flow to realize a large staff increment. As organizations move from just being successful to a stage of growth, the management of most companies “consolidates the company and marshals resources for growth. The owner takes the cash and the established borrowing power of the company and risks it all in financing growth” ([3]). If loaded annual technical head count cost is $100,000, and you bring on a team of five from outside the organization—knowing that it takes about six months for new hires to fully become integrated into the effort—it will take $300,000 just to get started. Additional time is likely to pass before revenues grow to cover the incremental staff cost. You can reduce the six-month interval if the teams are in-house, but an organization must be large to sustain a pool of teams that are available on demand. And scaling experts suggest that such a team needs experience in the domain of application and needs to already be working as a “high-performance team,” which further restricts the possibility that any available team might be a match for the work. [4]

Further, some national labor laws often make it very costly for firms to dismiss employees who have worked past their “probationary period” (usually six months). This means it is not cost-effective for firms to hire and fire teams at will unless they can easily assign the people to other internal efforts. That implies that the firm is large. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, companies with annual revenues of $1.2 million or less do 85 percent of all software development, which suggests they have five to eight employees. [4] They rarely have the in-house resources to “consolidate the company and marshal resources for growth.”

Therefore:

Differentiate a single large Development Team into two small teams after it gradually grows to the point of inefficiency—about seven people in the old team. Carry over the experience, domain and product knowledge, and culture of the original team into each new team.

It is important that each resulting team remain a Cross-Functional Team after the split, with broad enough coverage of disciplines to be able to autonomously deliver a Product Increment (see Autonomous Team). Each new team should have the authority to work on all parts of the product.

✥ ✥ ✥

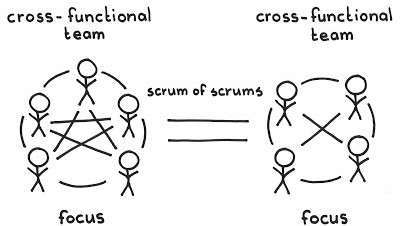

Each new Development Team should have its own ScrumMaster and developers. The new team works from the same Product Backlog as the original team, and works with the same Product Owner. The teams working on any given product still coordinate with each other and should share the same work environment (see Collocated Team), but each team should have autonomy to deliver each of the Product Backlog Items it takes into a Production Episode.

Members of separate teams should continue to coordinate with each other informally, and as necessary, through the daily rhythm of Scrum of Scrums events.

Sometimes the original team has a person who is the only specialist in some area necessary to the team’s success, which implies that the corresponding knowledge may be lacking in one of the resulting teams. Use Set-Based Design, Birds of a Feather, and Apprenticeship to remove the impediment as soon as possible; in the interim, the team just does its best to cover the missing area.

Growing from one team to two teams is hard. A rule of thumb is that you take about a 40 percent hit in velocity (see velocity) to support the coordination necessary for two teams to do the work of a single team made up of the same team members. The percentage may decrease as the number of teams increases, which suggests that it may make sense to scale only if one plans to scale big.

If it feels natural that one of the new teams supports its own stakeholder community, then consider Value Stream Fork or Value Areas.

Incremental growth, and ultimate differentiation into parts, is the fundamental process that underlies Christopher Alexander’s Theory of Centers and lies at the core of how he views harmonious growth of structure. He articulates the general principles in [5], and explores them more explicitly in Chapter 24 (“The Process of Repair”) of [6].

Keeping the team small helps to concentrate its sense of identity, which in turn fuels a positive sense of team membership (see Team Pride).

[1] Fred Brooks. The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering. Addison-Wesley: 1975.

[2] —. “Brooks’s [sic.] Law,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brooks's_law, April 2018 (accessed 5 June 2018).

[3] Neil C. Churchill and Virginia L. Lewis. “The Five Stages of Small Business Growth.” In Harvard Business Review 61(3), May-June, 1983, pp. 30–50.

[4] Carl Erickson. “Small Teams Are Dramatically More Efficient than Large Teams.” AtomicObject.com, https://spin.atomicobject.com/2012/01/11/small-teams-are-dramatically-more-efficient-than-large-teams/, 11 January 2012 (accessed 13 April 2017).

[5] Christopher Alexander. The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe, Book 1—The Phenomenon of Life. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2004.

[6] Christopher Alexander. “The Process of Repair.” In The Timeless Way of Building. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1979, Chapter 24.

Picture credits: The Scrum Patterns Group (Mark den Hollander).