...organizations, teams, and individuals bring things to Done (see Definition of Done) by working together on them. While it is the Product Owner’s responsibility to order the Product Backlog to maximize value delivery, it is the responsibility of the Development Team to order the implementation of the Sprint Backlog to maximize flow of production. (See Developer-Ordered Work Plan.)

✥ ✥ ✥

Working on too many things at once can radically reduce individual effectiveness, team velocity, or enterprise well-being. It can cripple velocity and can sometimes reduce it to zero. If everyone is working on their own thing individually, they are unlikely to help each other and, in the long term, learn from each other.

The personal preferences of a team member and impediments in the work environment often cause scattered effort. A team working on multiple items at once results in excessive work in process, low process efficiency and associated delays.

Work in process (WIP), work in progress (WIP), goods in process, or in-process inventory are a company's partially finished goods waiting for completion and eventual sale or the value of these items. These items are either just being fabricated or waiting for further processing in a queue or a buffer storage. The term is used in production and supply chain management.

Optimal production management aims to minimize work in process. Work in process requires storage space, represents bound capital not available for investment and carries an inherent risk of earlier expiration of shelf life of the products. A queue leading to a production step shows that the step is well buffered for shortage in supplies from preceding steps, but may also indicate insufficient capacity to process the output from these preceding steps. [1]

Consider a team that attempts to improve throughput with parallelism, with each person working on a single Product Backlog Item (PBI) at a time. Working alone, Development Team members are more likely to focus on building the item than on testing it, partly because both the expertise and appetite for testing are small relative to the creative tasks of designing and building. If multiple work items are delayed during a Sprint, there is an increased risk of not bringing the PBIs to Done by the end of the Sprint. Even worse, in Silicon Valley and in Europe, some teams working on complex software find that not identifying and fixing a bug in a Sprint can turn one hour of testing at code complete to 24 hours of testing three weeks later. If the team defers testing instead of Swarming, something that could be delivered in a month can take two years to deliver.

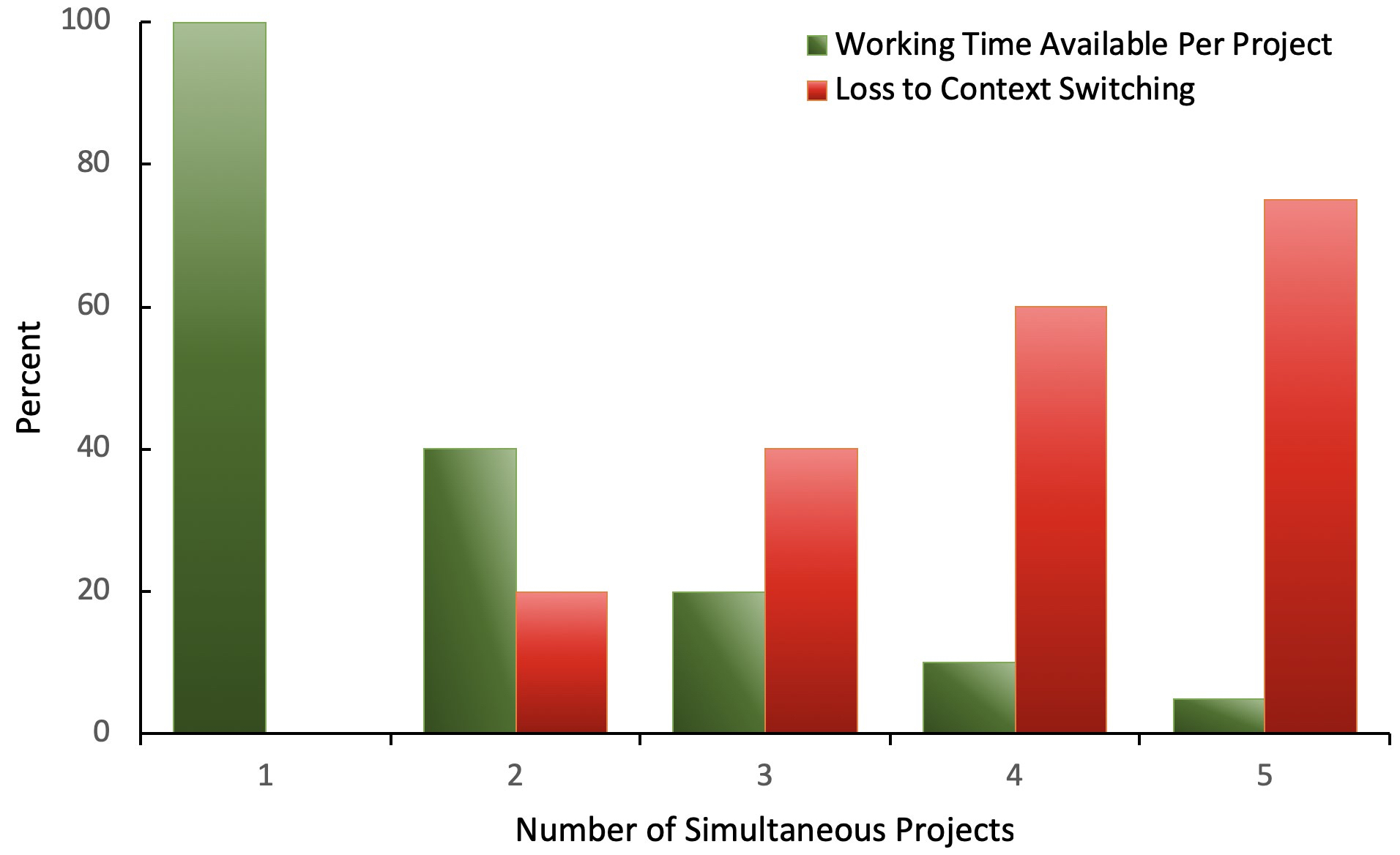

Compounding the problem, Jerry Weinberg offers this rule-of-thumb model on how multitasking delays getting things done ([2], p. 284):

Even worse, recent brain research shows that multitasking makes you stupid as well as slow, while increasing stress and accelerating aging ([3]).

Working on many things at once gives the illusion that things are going faster and plays on management’s desire for efficiency of the individual worker. Yet, this increases the number of defects that the team must fix and test later, escalates development costs, and slips release dates.

The team can divide work across subgroups, but each subgroup can work autonomously only to the degree that the work items are mutually independent. Items tend to be mutually coupled in a complex system, and dealing with these dependencies can block progress and add delay, though circular dependencies are rarely necessary when ordering work items. Development Team members often want to work independently to avoid stepping on each other’s code, a symptom of a dysfunctional team with poor process and engineering practices. Google solved this problem by implementing a daily meeting and Swarming to get things Done ([4]).

Therefore:

Focus maximum team effort on one item in the Product Backlog and complete all known work as soon as possible. Whoever takes this item is Captain of the team. Everyone must help the Captain if they can and no one can interrupt the Captain. As soon as the Captain is Done, whoever takes responsibility for the next backlog item is Captain.

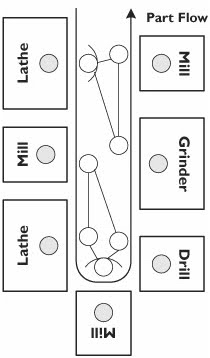

In 1947, we arranged machines in parallel lines or in an L shape and tried having one worker operate three or four machines along the processing route. We encountered strong resistance among the production workers, however, even though there was no increase in work or hours. Our craftsmen did not like the new arrangement that required them to function as multi-skilled operators. They did not like changing from “one operator, one machine” to a system of “one operator, many machines in different processes.” Taiichi Ohno, The Toyota Production System, 1988, Chapter 1. [5] — Figure from Liker, The Toyota Way, 2004, Chapter 8, Figure 8–4. [6]

This pattern is about maximizing velocity to deliver business value by getting the team to work together. It requires a mind shift to focus on flow of production by swarming on the backlog items instead of on the efficiency of a given task. Individual efficiency does not optimize production while slack can speed things up.

Paradoxically, while Swarming means that the team is focusing on one PBI at a time, it also implies a rapid interleaving of many development activities on the item in progress. The team may do a few minutes of implementation, followed by a short increment of testing, which may actually lead to additional analysis and subsequent eddies of development until the PBI becomes Done. Carrying out one development phase at a time is another way to avoid teamwork, and Swarming works best when all team members bring all their talents to bear all the time.

This is a fractal pattern and applies at the enterprise level, portfolio level, team level, and the individual level; see Covey ([7]). It leads to happier teams and cultural success.

✥ ✥ ✥

You can encourage a team to Swarm by keeping the team’s identity focused on the team as a whole rather than individuals. Limit or eliminate rewards for outstanding individual accomplishment. Work against a “hero culture” by eliminating overtime, overtime pay, and a work ethic that values working harder. Working together as a team on one PBI at a time will broaden team members into new skill sets and result in more multi-skilled individuals. It can also motivate the team to do something great every Sprint with a well-articulated Sprint Goal.

Working the highest priority PBI on the Scrum Board will tend to cause individuals and teams to self-organize to maximize flow in a Sprint. Systematic A/S in Denmark showed how implementing this pattern doubled the productivity of every team in the company ([8]). Citrix Online applied this pattern at the enterprise level and reduced release cycles from 42 months to less than 10 months resulting in substantial gains in market share for its products ([9]).

Implementing this pattern moves the team toward one-piece continuous flow. Toyota demonstrated that this optimizes production capacity:

In its ideal, one-piece flow means that parts move from one value-adding processing step directly to the next value-adding processing step, and then to the customer, without any waiting time or batching between those steps. For many years we called this “continuous flow production.” Toyota now refers to it as “one-by-one production,” perhaps because many manufacturers will point to a moving production line with parts in queue between the value-adding steps and erroneously say, “We have continuous flow, because everything is moving.” Such a misinterpretation is more difficult to make when we use the phrase “one-by-one production” ([10], p. 45).

Working on one Product Backlog Item at a time makes it unnecessary to coordinate between work items in progress. Instead, the team can work on the least dependent items first.

The team continuously adjusts its tack in a Developer-Ordered Work Plan. They come together as one mind to modulate this direction every day in the Daily Scrum. However, all direction adjustments happen within the terms of the Sprint Goal, which itself is a rallying point that can help channel the flow of the team. Mark Gillett, an experienced executive manager and technology investor, remarks, “Teams that behave as if there is a series of tasks (and perhaps handoffs) for individuals will see less value than those who identify needs for and dynamically partner to work a PBI to Done.” A team that works closely together builds a shared vision of what the product is and is able to grow pride in the product and in their achievement; see Product Pride.

Members of the Scrum community have also been talking about Swarming for many years. See, for example, Dan Rawsthorne’s work ([11]).

[1] —. “Work in Process.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Work_in_process (accessed 27 January 2019).

[2] Gerald Weinberg. Quality Software Management: Volume 1, Systems Thinking: New York: Dorset House, 1992.

[3] Darren Rowley and Manfred Lange. “Forming to Performing: The Evolution of an Agile Team.” In Proceedings of Agile 2007, Washington, D.C., 2007, pp. 408-414.

[4] Mark Striebeck. “Ssh! We're Adding a Process ...” In Proceedings of Agile 2006, Minneapolis, 2006, pp. 193-201.

[5] Taichi Ohno. Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production. New York: Productivity Press, 1988.

[6] Jeffrey K. Liker. The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the World's Greatest Manufacturer. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

[7] Steven Covey. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. New York: Rosetta Books, 2009.

[8] Jeff Sutherland, Carsten Ruseng Jakobsen, and Kent Johnson. “Scrum and CMMI Level 5: A Magic Potion for Code Warriors!” In Proceedings of Agile 2007, Washington, D.C., 2007, pp. 272-278.

[9] Dan Greening. “Enterprise Scrum: Scaling Scrum to the Executive Level.” In 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Kauaii, 2010, pp. 1-10.

[10] Mike Rother. Toyota Kata: Managing People for Improvement, Adaptiveness, and Superior Results. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010, p. 45.

[11] Dan Rawsthorne and Doug Shimp. Exploring Scrum: The Fundamentals, 2nd ed. N. Charleston, SC: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2011.

Picture credits: Shutterstock.com.