…you are ready to embark on a Sprint, and you are planning it in Sprint Planning.

✥ ✥ ✥

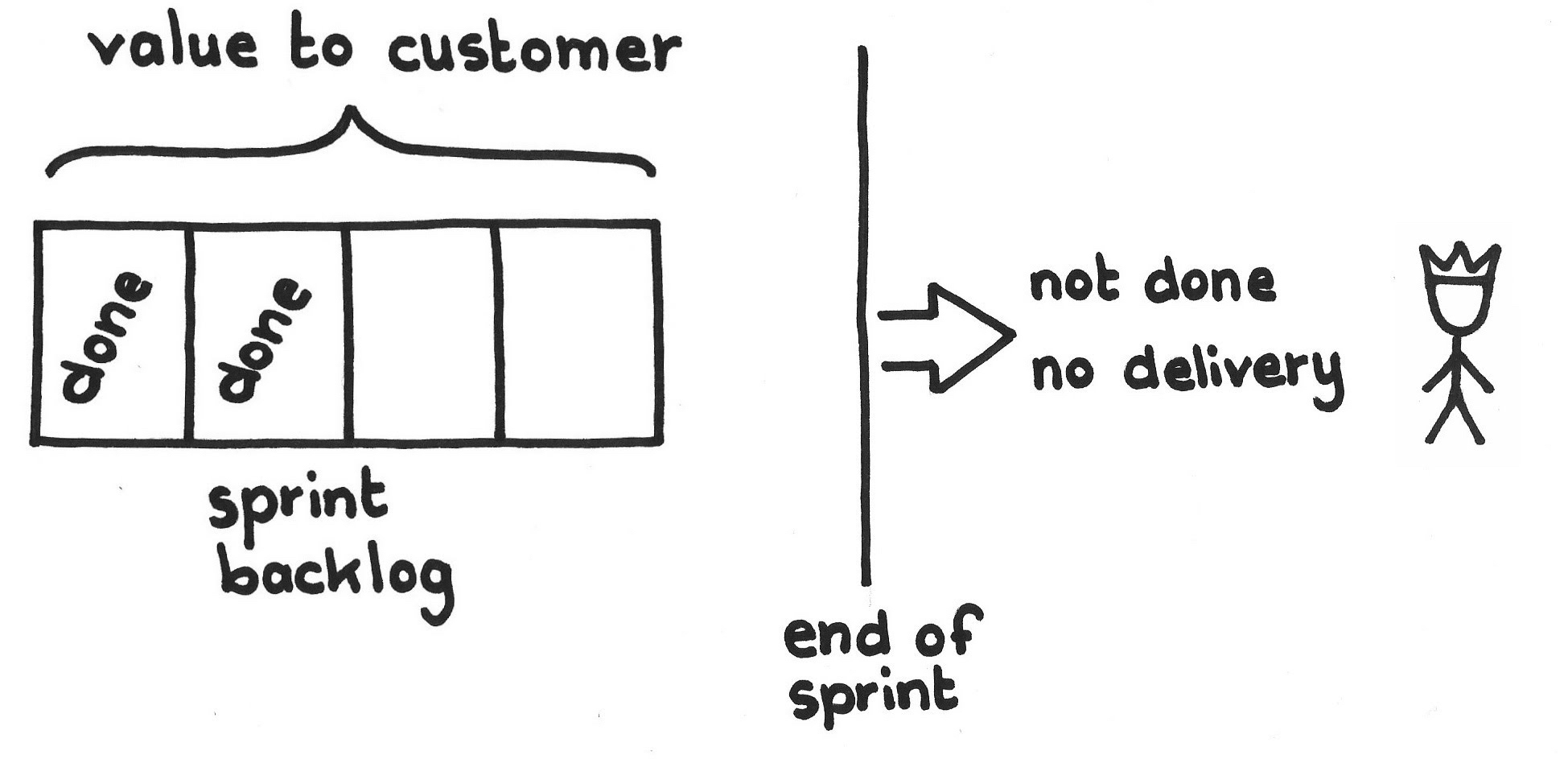

The objective of a Sprint is to deliver value to the stakeholders. However, simply following a list of Sprint Backlog Items (SBIs; e.g., tasks) does not necessarily result in the creation of the greatest value possible.

Because the team lays out its work plan in terms of individual tasks or deliverables, it’s easy for it to pick up an individual item and work on the item in isolation during the Production Episode. However, that dilutes the innovation that comes from the interactions between individuals who bring different perspectives to the work. Cubicle walls can become barriers to continuously communicating insights that are important to not only one developer, but rather to many developers (Development Team members) or to the entire team. Teamwork suffers.

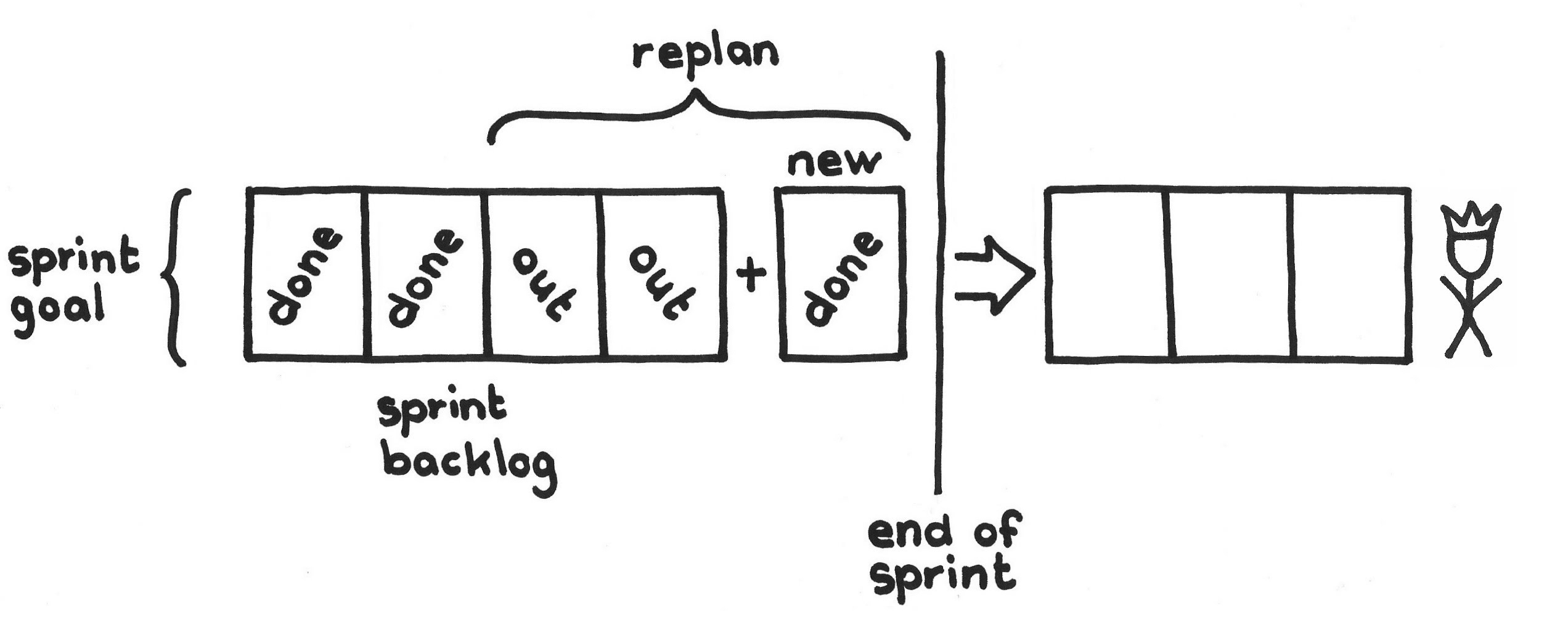

The team may need to partially replan a Sprint in progress to ensure that the team delivers value to the stakeholders at the Sprint’s end. New work may emerge from the team’s latest insights, and the team should update its plan accordingly. If the team would instead follow the original work plan, it might not create the greatest value possible. Another common occurrence is that partway through the Sprint, it becomes clear that the team will not complete every SBI in the Sprint Backlog. This is often because the work required to complete SBIs expands. The team still wants to deliver value if at all possible, and it may take replanning to do so. Replanning the work for the Sprint requires forethought and time.

Another scenario is that the team needs important technical knowledge about how to implement a Product Backlog Item (PBI) to know how to develop it with confidence. The developers (or even the Product Owner) may need a technical prototype to validate a proposed architecture or to learn performance characteristics of some technology. While a PBI should identify such work, its uncertain nature requires that the team focus on obtaining the knowledge rather than completing all planned work. The technical prototype becomes a critical path item for Sprint success.

In some cases, the greatest value might not be an explicit Product Backlog Item. To give one example, the greatest value for the team was to increase revenue per Sprint, and the team devoted a Product Backlog Item to this effort. On the other hand, sometimes the bulk of the Sprint’s value derives largely from one critical PBI out of many.

Therefore:

The Scrum Team commits to a short statement of the value it intends to create during the Sprint. This becomes the focus of all work in the Sprint.

The entire Scrum Team jointly creates the Sprint Goal. The Product Owner will naturally guide the creation of the Sprint Goal because he or she has the best view on the next step toward the Product Vision and on how to create the Greatest Value. The Scrum Team should commit to the Sprint Goal as something always within reach.

The Development Team creates one Regular Product Increment to meet the Sprint Goal of each Sprint.

✥ ✥ ✥

The Scrum Team can use the Sprint Goal to frame the selection of PBIs for the Sprint but in some sense the Sprint Goal is more important even than the sum of the individual PBIs. The Sprint Goal creates coherence in the PBIs, helping to create a valuable Product Increment. One good initial approach to a Product Backlog is to express it as a list of Sprint Goals, which the Product Owner and Development Team together elaborate into PBIs.

The members of Autonomous Teams must be able to manage themselves to accomplish their goals, and Developer-Ordered Work Plan states that Development Teams must be free to order their Production Episode work however they see fit. The Sprint Goal is the sole mechanism by which the Product Owner can influence the potential order in which the Development Team carries out its work (by inferring urgency from the importance conveyed by the Sprint Goal)—but, again, only with the Developers’ consent.

During Sprint Planning, the Scrum Team determines what they aspire to achieve by the end of the Sprint; that, in short, is what the Sprint Goal is for. The Development Team defines the details on how to accomplish this Sprint Goal by creating a Sprint Backlog. If the Development Team concludes that they cannot accomplish the Sprint Goal, it should refine the Sprint Goal with the Product Owner. A key output of Sprint Planning is that the Development Team should be able to explain how it can accomplish the Sprint Goal and how to know it has achieved the goal. The ability to explain comes through a thorough understanding of the work ahead, which raises the probability that the team actually can achieve the Sprint Goal within the Sprint.

The Development Team commits to the Sprint Goal. This Sprint Goal can help unify the Development Team (see Unity of Purpose), and it serves to build stakeholders’ trust in the team.

The Sprint Goal should be visible to the team; for example, put it on the Scrum Board or other Information Radiator.

The Development Team keeps the Sprint Backlog current during the Sprint to support meeting the Sprint Goal. Progress on the Sprint Backlog (such as indicated on a Sprint Burndown Chart) is like progress down the soccer field during a Sprint: though each yard of progress brings the ball closer to the end, the value comes in the goal. But it is sometimes possible to complete the Sprint Goal (in some way) without completing all SBIs. This helps teams handle contingencies and gives Developers flexibility in changing their work plan each day during the Daily Scrum. As an example: emergent impediments can threaten the Development Team’s delivery of the complete Sprint Backlog. In that case, the team automatically resorts to the Sprint Goal as “Plan B” without expending long hours replanning. A study performed by Carnegie Mellon University [1] reports that teams that prepare ahead of time for interrupts handle them 14 percent better than teams that don’t prepare. Teams that prepare for interrupts complete an uninterrupted task interval 43 percent faster than teams that don’t prepare. It’s a mindset to prepare for unplanned things: when they happen, teams can pivot to a new configuration to handle them, without external coaching.

It is theoretically possible to repeatedly achieve the Sprint Goal while completing only a fraction of the PBIs each Sprint. This should be uncommon, because the Sprint Backlog should align with the Sprint Goal; if not, there is a serious problem with the Value Stream.

Velocity (see Notes on Velocity) helps teams understand if they are doing things right (given the assumption that doing things right increases your velocity). The Sprint Goal helps teams ensure that they are doing the right things. It is about understanding the “why” of what the team is doing so that it can keep focus when things change.

Jeff Sutherland adds that in addition to keeping the team focused, the Sprint Goal encourages swarming (see Swarming): Can we get everyone working on one thing together? He relates:

In Silicon Valley in 2007, Palm was working on a Web OS that was later acquired by Hewlett-Packard. Sprint to sprint the teams were doing well until they appeared to hit a wall in a couple of Sprints. PBIs were not getting finished. Developers were demotivated and going home early. I was brought in and got the Product Owners and ScrumMasters to spend an hour interviewing team members on why they were demotivated. We found that they did not understand the reason they were working hard on low-level PBIs.

We spent an afternoon cleaning up the Product Backlog showing a clear linkage between high-level stories and the decomposition hierarchy. As soon as the developers understood that the Sprint Goal was to improve performance of the Web OS by 10%, they were motivated to complete the low-level stories and velocity went back up to normal.

Understanding why the PBIs are being implemented is critical for developers, particularly for expert developers who would prefer to go surfing if they don’t see the reason for their work.

The Sprint Goal usually relates to product value. The team can alternatively define Sprint Goals in terms of process goals—for example, doing all programming through pair programming, or showing up ontime for the Daily Scrum every day.

Repeatedly driving to the Sprint Goal motivates the team to a higher level of engagement; conversely, the Happiness Metric can be an effective tool to define or suggest Sprint Goals.

In 2001, Ken Schwaber and Mike Beedle were the first to describe the Sprint Goal ([2], p. 48).

[1] Bob Sullivan and Hugh Thompson. Gray Matter. “Brain, Interrupted.” In New York Times, 5 May 2013, page SR12, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/05/opinion/sunday/a-focus-on-distraction.html (accessed 2 November 2017).

[2] Ken Schwaber and Mike Beedle. Agile Software Development with Scrum (Series in Agile Software Development). London: Pearson, Oct. 2001, p. 48.

Picture credits: Shutterstock.com.