...a Scrum Team has come together and it is ready to start, or has started a Sprint. As such, the Development Team has created a Sprint Backlog and is working to achieve the Sprint Goal. Yet, in the words of German Field Marshall Helmuth von Moltke, “no plan of operations extends with any certainty beyond the first contact with the main hostile force.” In short, plans created during Sprint Planning become almost immediately obsolete.

✥ ✥ ✥

The team makes progress in a Sprint by finishing Sprint Backlog Items, but given the complexity of the work, the characteristics, size, and quantity of tasks change frequently—sometimes minute by minute.

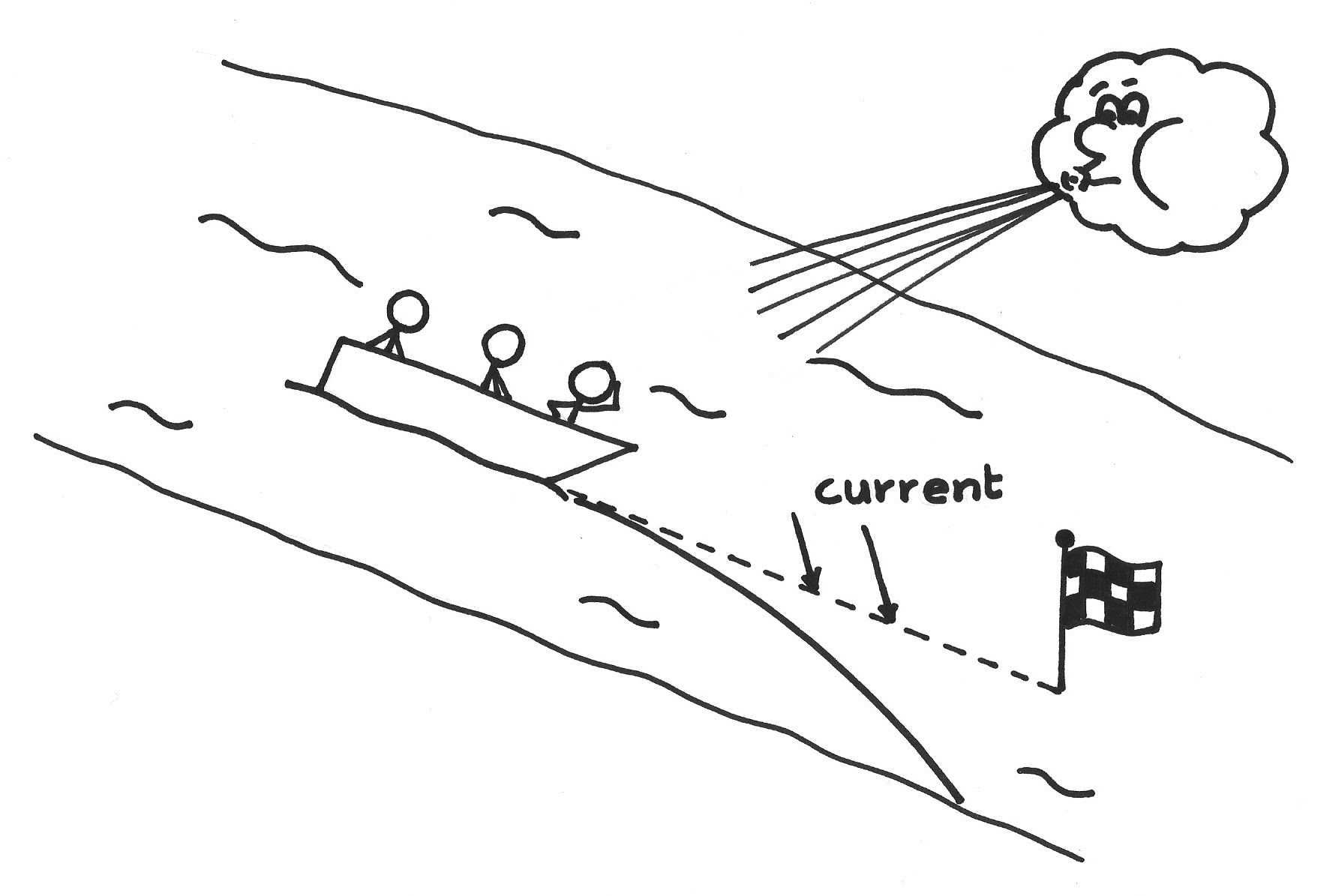

For example, alternative solutions, needed but unknown knowledge, hidden tasks, misunderstood requirements, requirements requiring further elaboration, dependencies among developers, or problems in the form of blockages may emerge in the team’s day-to-day work. The problem is how to cope with these issues in an effective way.

There are 9 x 10157 ways to order 100 tasks, yet only a few of these ways will put the team “in the zone” where work becomes effortless and velocity significantly increases (see Notes on Velocity). Because of the changing nature of the work, the team needs to adopt a new ordering at least once a day to move beyond mediocrity.

In addition to the work, team member absences (such as a sick day) may force the team to reconsider its work plan.

On the other hand, too much replanning and re-estimating wastes time and suffocates developers. But too little replanning and re-estimating leads to blockages that cause delays or obsolete plans that no longer represent reality.

Individuals can make decisions very quickly, but in a team environment it is impossible for individuals to take decisions in isolation. You need engagement with everyone who might be affected by the decision. It takes time to get agreement from all such parties.

An individual may need to bring up an issue to the whole team. But it may be difficult to find an opportunity to do so. In particular, issues continue to be impediments until the team fixes them.

Therefore:

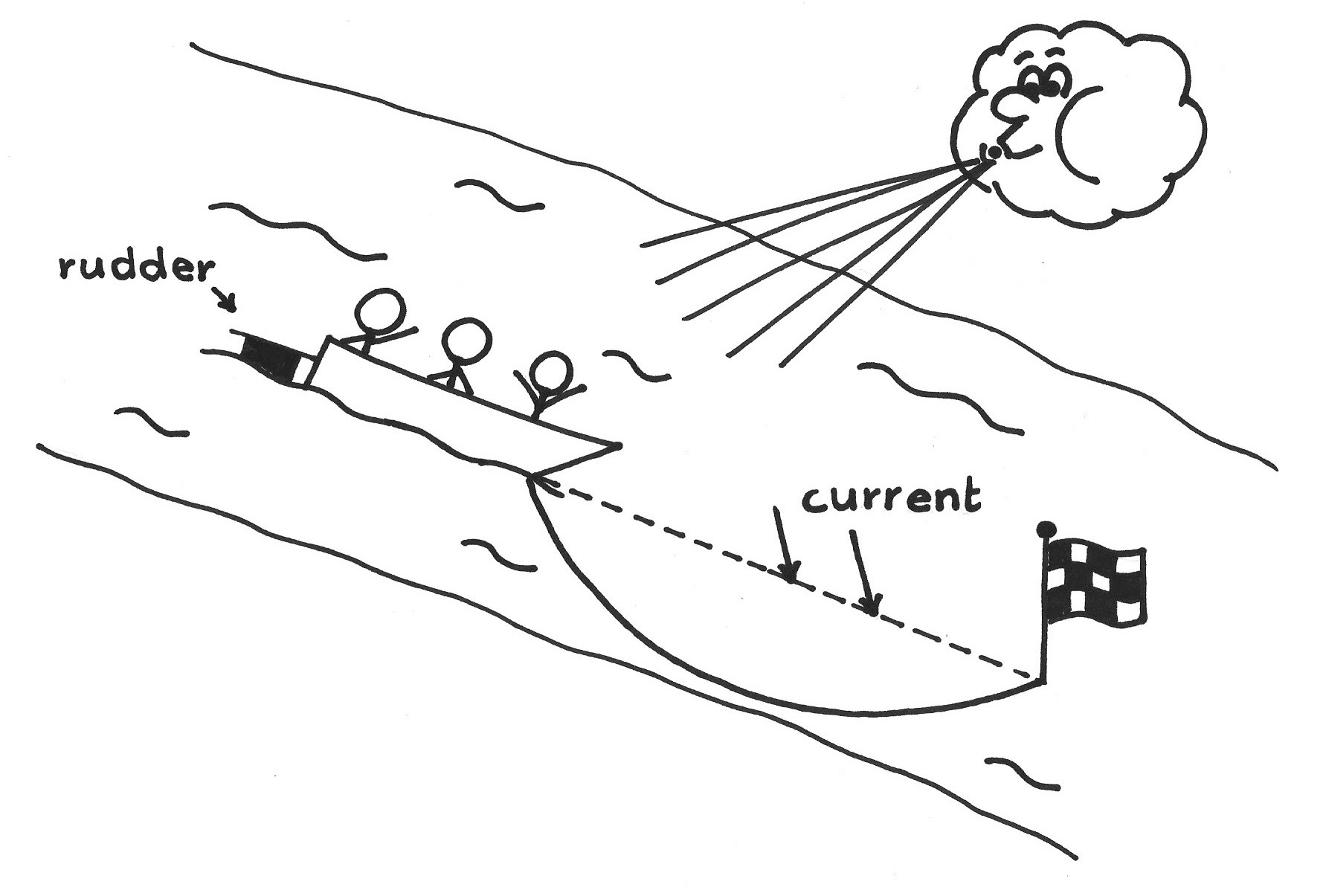

Have a short event every day to replan the Sprint, to optimize the chances first of meeting the Sprint Goal and second of completing all Sprint Backlog Items. Strictly time-box the meeting to keep focus on the daily plan and to avoid robbing time from development. Focus on the next day’s work but keep the remainder of the Sprint in mind.

Keep the meeting to 15 minutes or less. The team manages itself to its time box, and the ScrumMaster will enforce this aspect of the process if necessary. Many teams stand during the meeting to emphasize the short duration of the meeting. The team can continue afterward to take care of business unfinished in the Daily Scrum, but to spend more than 15 minutes a day on such replanning is a sign of need for Kaizen and Kaikaku.

It is vital that every member of the Development Team attend. In the rare occasion that a developer needs to be absent because of illness or conflict, it probably doesn’t make sense to send a substitute; the team will bring the developer up to date at the next Daily Scrum, at the latest.

In order to plan, you must know where you are, as well as what problems are standing in the way. And you need a complete picture. One popular technique is for each person in the Development Team to answer the following three questions:

- What did I do yesterday that helped the Development Team meet the Sprint Goal?

- What will I do today to help the Development Team meet the Sprint Goal?

- Do I see any impediment that hinders me or the Development Team from meeting the Sprint Goal?

Note that as developers voice impediments, there is a natural tendency to delve into them and explore possible solutions. But this meeting is for replanning and decision-making, not for problem-solving. Instead, a few members of the Development Team might agree to meet during the day to work out the solution—thus not wasting everyone else’s time. They will report what they have done at the next day’s Daily Scrum.

Of course, impediments often force changes to the plan. So the team adjusts its plan for the day to get around the blockages. That is one thing this meeting is all about.

This is the Development Team’s meeting. People outside the Development Team may attend the Daily Scrum at the invitation of the Development Team. The Development Team may wish to consider that there is a spirit of transparency in Scrum. But on the other hand, outsiders may influence the meeting by their very presence. In any case, only the Development Team actively participates in the meeting. This applies to the Product Owner as well as any other person not a member of the Development Team.

The ScrumMaster may attend the meeting at any time, especially in the early days of Scrum in the organization, mainly to enforce time-boxing and other aspects of the process. But too often the Development Team will start treating the ScrumMaster as a manager at these meetings. In that case it is better that ScrumMasters excuse themselves from these meetings, or that they take on the role of a ScrumMaster Incognito when they do attend.

The Daily Scrum results in an updated Sprint Backlog, as well as associated Information Radiators. However, it is crucial to understand that the Daily Scrum is a replanning meeting and not a status meeting. Radiated information is a by-product of rather than the aim of the meeting.

✥ ✥ ✥

The ethos of the Daily Scrum is a reality check: will we meet the Sprint Goal? The result of the Daily Scrum is a new daily plan grounded in reality, and generates a team that is more prone to cooperate and that has a better shared vision and understanding of what they are doing together. The team becomes better attuned to the landscape of impediments in which it is working.

The ritual of Daily Scrums helps a sense of team identity emerge from a group of people. It brings them together to refocus on their shared purpose and common identity. It reinforces team morale (see Team Pride). In some way, it is a daily version of an earlier published pattern that advises team members to first coordinate the broad issues over the table before drilling down into work tasks individually: see Face-to-Face Before Working Remotely.

Special activities such as Emergency Procedure will likely originate from discussions in the Daily Scrum.

Daily Scrums have additional benefits as well:

- Reduces time wasted because the team makes impediments visible daily;

- Helps find opportunities for coordination because everyone knows what everyone else is working on;

- Reinforces a shared vision of the Sprint Goal;

- Promotes team jelling by ensuring at least one global interaction every day;

- Promotes knowledge sharing and the identification of knowledge gaps;

- Increases the overall sense of urgency;

- Encourages trust and honesty among developers through a verifiable daily status; and,

- Strengthens the culture of the Development Team through shared rituals and encouragement of active participation.

The term stand-up meeting has a long tradition, and was reportedly used at events where Queen Victoria of England was present: it was necessary to stand in the presence of the queen. The Scrum practice has its roots in Coplien’s analysis of the Borland Quattro Pro for Windows (QPW) project ([1]), which had a remarkable track record in rapidly producing value and quality. Bob Warfield was running the project at the time and offers the following reflection:

It was a crucial part of our productivity, and today it is a cornerstone of Agile/Scrum where it is called a “Standing” meeting or a “Stand Up” meeting. Apparently some folks took it a bit literally and started doing the meeting without chairs. That’s fine, I think I’ll keep the chairs in my meetings, but they’re short enough that not having chairs shouldn’t be a problem. I used to tell people to get them to the meeting on time that there’d be two fewer chairs than attendees, but that was just my lame joke and I don’t recall actually ever doing that.[2]

The first Scrum team implemented the daily meeting in February 1994 based on the QPW initiative. The Scrum team concluded that the daily meetings at Borland were instrumental in achieving extraordinary performance. The Scrum team implemented daily meetings during its second monthly Sprint. In March 1994, the team pulled the same amount of work into the Sprint as the previous month, and completed it already during the first week. Since then, effective daily meetings have significantly improved the velocity of Scrum teams worldwide.

One last note: Laypersons often equate “doing Scrum” with having the Daily Scrum. While the Daily Scrum, at the Scrum Board, is one of the most noticeable events of Scrum organizations, there is much more to Scrum than can be characterized by the use of any set of tools. By analogy, kicking a football around in a park can look a lot like playing football, but it isn’t football. This pattern refers to many other patterns that represent crucial components of the Scrum framework, and yet those, too, are only a starting point.

This pattern is an evolution of the previously published Stand-Up Meeting.

[1] James Coplien and Jon Erickson. “Examining the Software Development Process.” In Dr. Dobbs Journal of Software Tools 19(11), October, 1994, pp. 88–97.

[2] Bob Warfield. “How I Helped Start the Agile/Scrum Movement 20 Years Ago.” Smoothspan Blog, 2 October 2014, https://smoothspan.com/2014/10/02/how-i-helped-start-the-agilescrum-movement-20-years-ago/ (accessed 14 February 2019).

Picture credits: Photograph by Walker Lewis, 1944, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USW3-055963-D.