Alias: Development/Delivery Team

...coming out of The Mist, the Product Owner has a product Vision whose realization is beyond the reach of any individual. The Product Owner is either working alone at the forefront of a new venture or working in the company of people who share passion for the same Vision. The fledgling effort might have formed in The Mist and needs to come together. The effort is at a point of taking steps to turn the Vision into a reality, both by coordinating the work of the longstanding members of the group and by potentially involving new people. Together, they seek a way to balance their collective identity with individual development responsibilities: to connect to each other under a framework that manages time and talent to support the business and create a rewarding workplace.

✥ ✥ ✥

Many great endeavors cannot achieve excellence through individual effort alone; the greatest power in production comes from teamwork. Great individuals can produce great products, but starting with a single individual makes it difficult to scale later. Each new person detracts from the effectiveness of everyone else on the team by about 25 percent for about 6 months (rule of thumb from James Coplien). Some products simply cannot realize greatness at the hands of a single individual, and without good feedback it is easy to get blindsided. Experience shows that person for person, teams outperform individuals: many hands make light work. While industry data show a range of 10 to 1 in individual programmer to teams output ([1], pp. 567–74), other data show that some teams outperformed others by a factor of 2000 to 1 ([2], p. 42).

On the other hand, it’s difficult to form a consensus direction across an overly large group—too many cooks spoil the broth. A development department composed of handfuls of people can eventually achieve consensus, but usually can do so only with long mutual deliberation and socialization. Such delay is intolerable in a responsive business.

In the lean startup model, everybody does everything, whether related to business, process, or production. The problem is that market shearing layers (different segments of the market whose needs evolve at different rates) and rates of change can be different than those of development. Market analysis and planning can play out over several months, while development for the market typically follows a monthly rhythm (Follow the Moon) and can be as short as a day or even hours or minutes for live customer emergencies. So putting both functions in one tightly coupled organizational unit puts stress on people and on schedules. Such a model is not sustainable as the enterprise grows.

Organizations need to run on multiple cadences. One cadence may be the day-to-day work of creating a product; another may be the longer cycles of working with the market. Role differentiation should primarily follow from variations in these cadences, according to the ‘‘Role Theory’’ chapter in [3] (pp. 488–567). History, experience, and inclination draws individuals to particular roles, which may lead to problems for organizations because roles may not work to the needed cadences. The organization needs to work coherently.

Therefore:

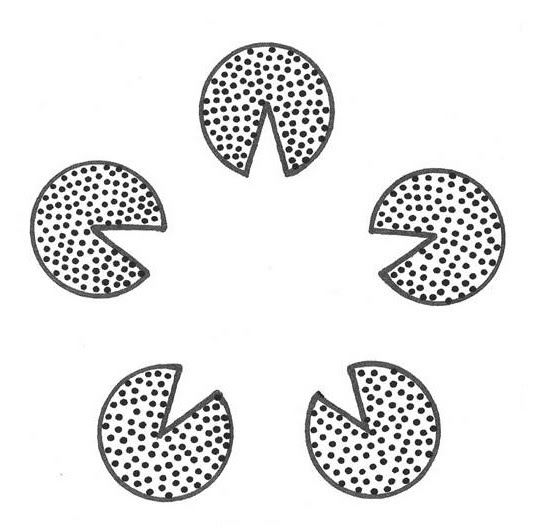

Building on Stable Teams, create a Development Team that rallies around a product inspired by the Product Owner’s Vision, to deliver successive increments of that product through the Value Stream to its end users. The team is a bonding of approximately five collocated individuals (see Collocated Team and Small Team) committed to working with each other towards a common goal.

The team is autonomous: self-selected, self-organizing, and self-managing. Give the individuals a collective identity to realize the Product Owner’s Vision. The Product Owner can tell them: “This is your product—do it.”

✥ ✥ ✥

The individuals forge a new identity tied to the product Vision while honoring each other’s identity within the new organizational unit. It’s not about scaling individual potential to raise productivity to some production level. It is rather about changing the paradigm of development to that of a collective mind, a Whole that can achieve more than the sum of the individuals.

You can build the team either top-down or bottom-up, but in either case you need a Vision to seed the team. In the top-down approach, the Product Owner hires the team after securing funding for the effort. The bottom-up approach arises from a setting like that of a lean startup: We are a bunch of nerds and we struggle to respond to the market and we want to be identified as the development team. Who do we respond to? The Product Owner. How do we work? From the top of the Product Backlog. The team can further evolve according to the Scrum framework with the introduction of other patterns, as described in the rest of this pattern.

If you don’t yet have a stable candidate team in place, then strongly consider building a Self-Selecting Team from available personnel, from scratch, and/or from the market. Look for a community of trust (see Community of Trust): if the trust doesn’t yet exist in the current set of individuals, it will be the first thing the group will need to take care of.

We generically call the team members Developers to avoid any labeling or compartmentalization that might violate the not-separateness of the Whole. A Developer works as a member of only a single Development Team. The team minimizes specialization and has no internal subteams but rather has undifferentiated membership. Scrum avoids any kind of assembly line structure within teams or across teams, with all work for each deliverable taking place within a single Development Team. This means that, for example, there is no separate testing team, and no separate team to bridge development with operational aspects of development such as product configuration. As early as possible, strive to build a Cross-Functional Team that has the skill set and talent, or the appetite to develop the skills and talents necessary to building a succession of complete, Done product increments (see Definition of Done).

Though Scrum tradition recommends team sizes of seven plus or minus two, effective teams tend to be smaller. The pattern Size the Organization (from [4], Section 4.2.2, “Size the Organization”) recommends a membership closer to five. Our experience suggests that the best Development Teams may comprise as few as three developers.

A Development Team should work as one mind, focused on the Sprint Goal and swarming together around individual increments of development, rather than individually “putting in their time at their station” (see Swarming). The team convenes a daily event to replan work in progress, called The Daily Scrum.

Small efforts sometimes arise to meet isolated, short-term business needs. In such cases it might be overkill to build a team; consider Solo Virtuoso.

As mentioned earlier, the team can differentiate itself by evolving according to the Scrum framework with other patterns. The Product Backlog guides the team’s work to produce Regular Product Increments in time-boxed development intervals called Sprints. Team members create their own work plan (Sprint Backlog) for each Sprint and manage themselves during the production part of a Sprint. During the production part of a Sprint, protect the Development Team so its members can work as an Autonomous Team and manage their work as a Self-Organizing Team. The Product Owner and a ScrumMaster provide such protection, as well as encouragement, support, and process guidance.

[1] Steve McConnell. “What does 10X mean?” In Andy Oram and Greg Wilson, eds., Making Software. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly, 2010, pp. 567–74.

[2] Jeff Sutherland and J. J. Sutherland. Scrum: The Art of Doing Twice the Work in Half the Time. Crown Business, New York, 2014, p. 42. Based on work by Lawrence H. Putnam and Ware Meyers in Five Core Metrics, Dorset, 2003.

[3] Theodore R. Sarbin and Vernon L. Allen. ‘‘Role Theory.’’ In Gardner Lindzey and Elliot Aronson, eds., The Handbook of Social Psychology, 2nd Edition. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1968, pp. 488–567.

[4] James O. Coplien and Neil B. Harrison. “Size the Organization.” In Organizational Patterns of Agile Software Development. London: Pearson, 2004, Section 4.2.2.

Picture credits: Shutterstock.com.