...the team is done with Sprint Planning, and you have a Sprint Backlog that defines the work plan. You are striving to deliver the Product Increment and are aiming for the Sprint Goal.

✥ ✥ ✥

Team members do the best work, and most efficiently complete planned work, when they can work together without distractions.

On one hand, it’s good to feed development with just-in-time understanding about the work at hand. On the other hand, constant interruption brings certain disruption at some cost. Being in flow is good, and even a well-intentioned disruption to deliver a helpful requirements update may cost the Development Team some time to restore flow. It isn’t clear whether the increased market value from a disruptive requirements correction will ever offset the impact to development cost. In any case, constantly disrupting a Development Team to “help” it with clarifying input takes the team out of flow and substantially reduces the value of each Sprint outcome.

Things rarely go well if the team receives both a list of work to do and a deadline by which it must be completed: motivation, quality, and efficiency all suffer ([1]). But to work with no sense of urgency or knowledge of the time available also leads to underachievement. [2]

Agile says that we should respond to change, but a system that reacts to every small external change can become a system that is out of control. Flexibility may be a business goal, but constancy and stability are enablers of effective work.

When the date to deliver work is not in the near future, people tend to have less focus and postpone important activities. (Just remember when you had to prepare for a test in high school, when you would start studying really hard the day before the exam.) In development, this could mean that in the early days you would focus on things that are easy or the most fun and you would not work on the most valuable Product Backlog Items (PBIs). Parkinson’s Law captures the end result that “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.” [3]

Therefore:

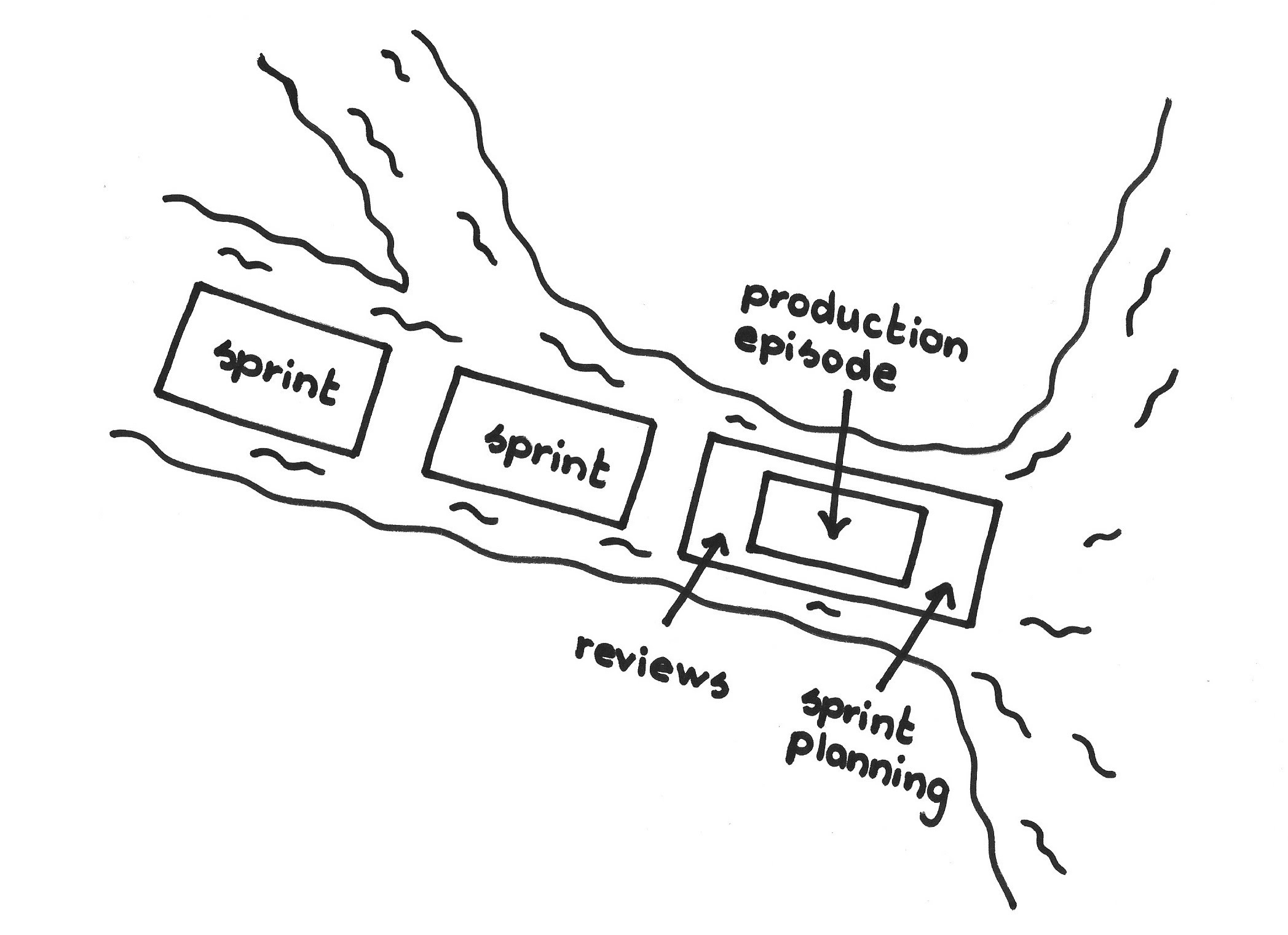

Compartmentalize all market-facing product realization work in a time-boxed interval, with participation limited to the Development Team. This uninterrupted development interval falls between Sprint Planning and the Sprint Review. During this interval, the developers take a few short scheduled discussions with the Product Owner to work toward a Refined Product Backlog—but on the whole, this is otherwise uninterrupted time.

During the Production Episode, the team focuses on the Sprint Goal and strives to achieve its forecast to complete all work on the Sprint Backlog. There is an agreement between the Product Owner and the Development Team that the PO may neither add nor change a PBI during the Production Episode. This ensures that the Development Team remains focused and committed so that there is enough stability to work on what is most important: the Sprint Goal. The Product Owner can change the long-term product direction by reordering the Product Backlog, but changes to the Product Backlog have no effect on the Development Team’s work plan until it processes the Product Backlog content at the Sprint Planning event at the beginning of the following Sprint. This motivates the Product Owner to think carefully about what is most valuable to work on, and to not waste time and money developing less valuable PBIs.

All but the most disciplined Scrum Teams should disallow their delivery scope from changing during the Production Episode (except for continuing to pull from the top of the Product Backlog when finishing early). More advanced teams may find efficient ways to negotiate between the Product Owner and the Development Team, in ways that both still find positive and fair. Frequent changes in scope or interruption by management or the Product Owner can cause the team to lose motivation and can be a sign that the business is not faithful to the Vision.

During Sprint Planning, the Development Team members forecast (not “commit”) the volume of work they feel they can complete during this Sprint and pull that amount of work into the work plan (Sprint Backlog), so the interval is a “gift from the project” rather than an externally imposed completion constraint. New work may emerge from unforeseen requirements or defects during the Production Episode, and the Development Team may update its Sprint Backlog accordingly. This emergent work tends to remain about the same in volume across Sprints and, while taken into account by the Developers during the Sprint, there is no attempt to estimate it or account for it in advance. Such effort is absorbed into the team’s estimates when using common estimation practices, such as described in Estimation Points and Notes on Velocity.

The duration of the Production Episode is the length of the Sprint less the time allotted to Sprint Planning, the Sprint Review, and the Sprint Retrospective. Four weeks is the upper bound on the length of a Sprint, and they typically last two weeks.

During the Production Episode, the Development Team assesses progress and replans the Sprint in the Daily Scrum. Every day, the Development Team updates the Sprint Backlog with a revised Developer-Ordered Work Plan optimized to achieve the Sprint Goal. Teams also maintain a discipline of Good Housekeeping.

✥ ✥ ✥

At the end of a successful Production Episode, the team reaches the Sprint Goal and realizes a new Product Increment that is ready for the Sprint Review. Some Sprint Backlog Items may remain in the Sprint Backlog at the end of the Production Episode, but the Development Team has completed enough of the backlog to have achieved the Sprint Goal. If the Development Team finishes early, it pulls additional work from the top of the Product Backlog, breaks the work down into a work plan, and continues with the Sprint. When a Sprint becomes in danger of not delivering the entire Sprint Backlog, the team should resort to the Sprint Goal. The team assesses this risk and responds accordingly every day at the Daily Scrum.

The PBIs that reach a state of Done (see Definition of Done) during a Sprint become delivery candidates for that Sprint or a subsequent Sprint. Scrum separates the decision of whether something is Done from the decision of whether to deploy; the Product Owner decides when to release a PBI to the market. The Scrum Team produces a Product Increment at the end of the Sprint that is most often the key candidate for delivery, but more frequent delivery (e.g., of emergency repairs) is possible: see Responsive Deployment. Making PBIs small enough raises the chances that several of these become deliverable every Sprint.

A failed Sprint is one in which the Scrum Team does not achieve the Sprint Goal. Some practitioners avoid using the term failed and instead might say “A Sprint that did not achieve the Sprint Goal.” It is possible (but unlikely) that the team nonetheless emptied the Sprint Backlog. Neither The Scrum Guide [4] nor any broad practice recognize any distinction in action that follows from failed and nonfailed Sprints, but the distinction helps underscore the importance of process improvement as the team discusses the Sprint during the Sprint Retrospective.

The team’s velocity (see Notes on Velocity) is the amount of work that the team can complete in a single Sprint. It is a measure of the team’s demonstrated capacity to complete work in a Sprint and is usually a measure of relative (or, sometimes, absolute) work per Sprint. The team establishes its velocity based on averaged recent historical performance; given Yesterday’s Weather, the team’s delivery should be in line with the expectations it sets when creating the Sprint Backlog. Because velocity is a stochastic value, about half of the Sprints will finish all Sprint Backlog Items early (before the Sprint is over) while half will miss the mark. Good teams learn to use Yesterday’s Weather to avoid taking too much into the Sprint and thereby risking not delivering everything; good disciplines such as described in Teams That Finish Early Accelerate Faster will improve a team’s delivery track record.

In exceptional cases, particularly when it becomes impossible to meet the Sprint Goal, the Product Owner may shorten a Sprint: see Emergency Procedure.

The pattern name honors Ward Cunningham’s “Development Episode” pattern, which is also about framing of work. [5]

[1] Teresa M. Amabile, William DeJong, and Mark R. Lepper. “Effects of externally imposed deadlines on subsequent intrinsic motivation.” In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 34(1), Jul. 1976, pp. 92--98.

[2] This simulation was a predecessor of: John Sterman, David Miller, and Joe Hsueh, “CleanStart: Simulating a Clean Energy Startup.” MIT Management, Sloan School, Leading Edge, https://mitsloan.mit.edu/LearningEdge/simulations/cleanstart/Pages/default.aspx, accessed 1 April 2019.

[3] —. Parkinson’s Law. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parkinson's_law (accessed 2 November 2017).

[4] Jeff Sutherland and Ken Schwaber. The Scrum Guide. ScrumGuides.org, http://www.scrumguides.org (accessed 5 January 2017).

[5] Ward Cunningham. “EPISODES: A Pattern Language of Competitive Development.” http://c2.com/ppr/episodes.html, ca. 1995, accessed 17 April 2018.

Picture credits: Shutterstock.com.