...you are building a Product Backlog from items that will drive your business. The Vision is in place and the Product Backlog may contain early informal notions of market releases or Sprint Goals.

✥ ✥ ✥

You want to best organize work to optimize the product’s value (Return on Investment, Net Present Value, etc.; see Value and ROI). Scrum focuses a lot on how to organize work, and it’s obvious that “doing things right” contributes to solid value. However, Value and ROI may relate even more strongly to stakeholders and to “doing the right thing.”

More broadly, value comes from delivering something of worth to stakeholders. An enterprise has many stakeholders: customers, end users, shareholders, marketing and sales, support, designers, architects, developers, and testers, each of whom contributes to an overall sense of value and stands to benefit from the ongoing creation of Product Increments.

An ideal system increases value for all of the stakeholders, rather than benefiting one at the expense of the other. While everyone may have to give something (time, money, work), we want to achieve the paradox that everyone gets more than they give—or, at least as reduced to cynical terms, that everyone gets as much as they give.

Therefore:

Create distinct specifications of changes and additions to the product, called Product Backlog Items (PBIs), that together form the Product Backlog. Each PBI describes something that the Developers can develop and deliver to add value to relevant stakeholders when Done (see Definition of Done). The most common stakeholder is the market, or its representative—the Product Owner. However, a PBI may describe work that reduces cost to the enterprise or reduces effort for the Development Team, or a tool that helps the Product Owner Team better do its work. A PBI can describe anything that has potential value to a stakeholder.

A PBI should have a name or other designation that helps relevant stakeholders crisply recall what the deliverable encompasses. A good PBI captures the stakeholder-facing decisions that the Product Owner has taken, or agreements between the Product Owner and Developers—the things they should write down to help them together remember. A good PBI has development estimates provided by the Development Team that will implement it, as well as notes about the PBI’s contribution to value.

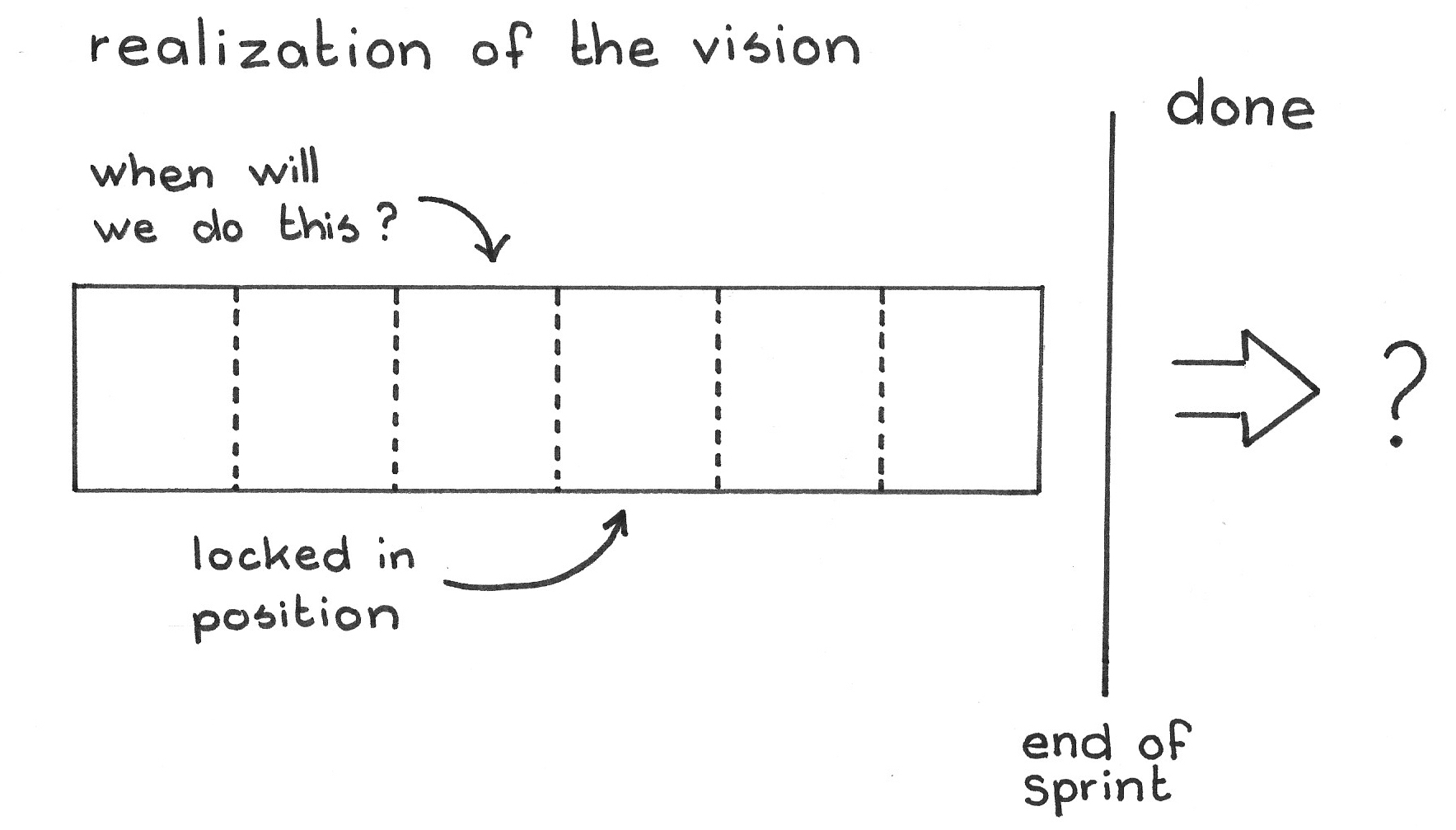

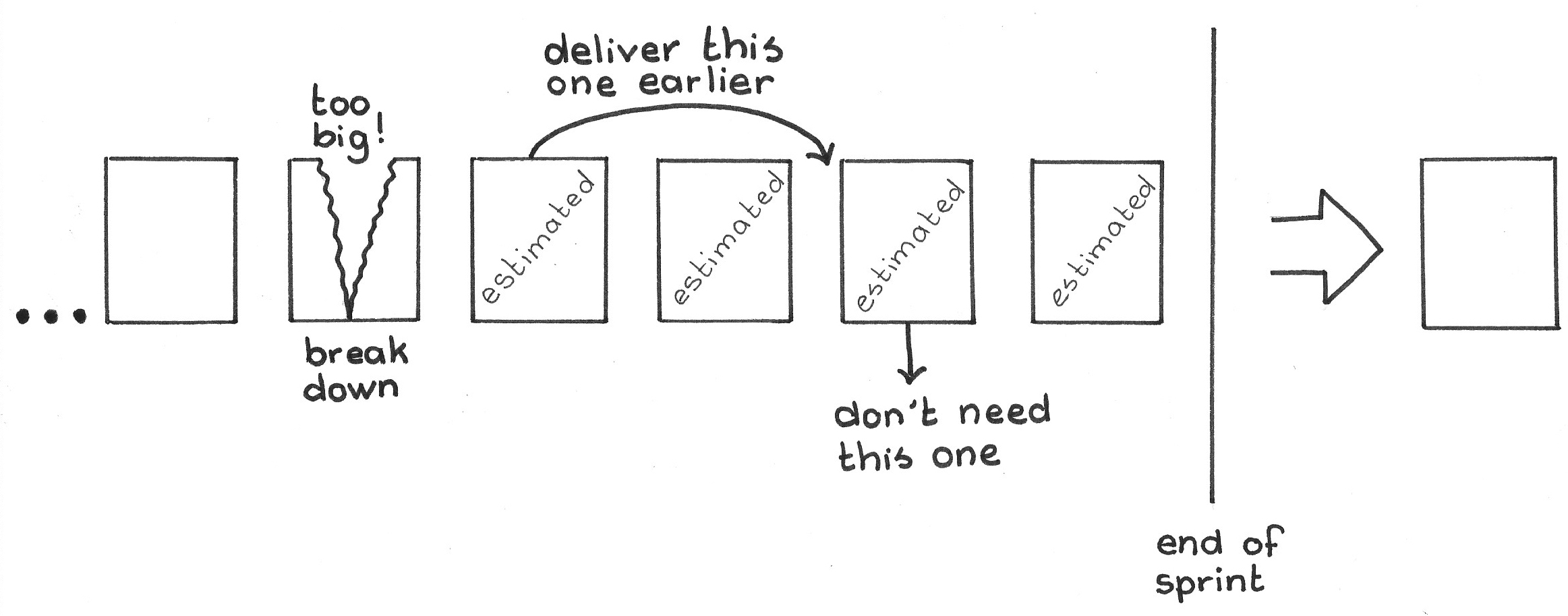

The PBI is the focal point of Scrum deliverables. The lifetime of a Scrum deliverable starts with the Vision, which the Product Owner breaks down into Sprint Goals that correspond to Product Increments. The Scrum Team breaks down those Product Increments into PBIs, which are the most granular unit of delivery in Scrum, working with the Product Owner as required (see Refined Product Backlog). The Product Owner, with support from the rest of the team, brings PBIs to a status of Ready (see Definition of Ready) — clearly specified, valuable, and worthy of development. The PBIs together drive the implementation of the solution described in the Development Team’s work plan, the Sprint Backlog. PBIs that achieve the stature of Done are delivery-ready.

✥ ✥ ✥

A PBI is usually one piece of a larger Product Increment, and the focus of the best PBIs is on a product solution that lies in the Product Vision rather than on the requirements behind that contribution to the increment. The Scrum Team and the Product Owner discuss the requirements behind each deliverable face-to-face as they together make the backlog Ready. The team and other stakeholders can employ user stories, story boards, interaction diagrams, prototypes, user narratives, and whatever tools they choose to shape a Product Backlog Item, but these artifacts in general are not themselves effective PBIs. For example, there may be many user stories for a single deliverable, each from a different stakeholder, that expresses the need and motivation of that stakeholder with respect to that deliverable. Yet it is the deliverable, and not its facilities, that should stand as the unit of administration, estimation, and delivery in Scrum—and the PBI represents that deliverable. The Scrum Team discusses requirement details face-to-face as they build a Refined Product Backlog and as they prepare for the Sprint at hand in Sprint Planning. So a good PBI represents a set of requirements rather than being a mechanism to communicate requirements. A good PBI memorializes one or more rich interactions between and among the Developers and the Product Owner, rather than itself being the vehicle by which the Developers learn requirements. That said, the PBI can serve as a home for details about scenarios, properties of size or weight or speed or time, that the team might forget: development decisions have more detail than a group of people can retain in their heads for two weeks. And though a good Product Backlog Item lives in the solution space rather than in the problem space, it falls short of specifying how to implement and deploy the solution. That is up to the Development Team.

While a PBI is a written artifact that appears on the Product Backlog, much of the information passed from the Product Owner to the Developers occurs verbally and interactively in Scrum planning events. A question-and-answer form of exchange, after an initial presentation by the Product Owner, is totally appropriate. A common pitfall is for the Product Owner to instead turn a PBI into a comprehensive document that developers can read to minimize the amount of interaction the Product Owner will need with the Developers. As a rule of thumb, PBIs should start lightweight and grow in detail and specificity as time progresses. The PBI may nonetheless carry detailed market information that will be important to realize the PBI (such as detailed response time requirements, or limitations on size or weight), because such information reflects a Product Owner or team decision on the nature of the deliverable.

The team should give special attention to PBIs near the top of the Product Backlog, which will soon go into a Production Episode. The Product Owner and Developers should discuss these to the point where Development Team members view them as Enabling Specifications.

Make sure that the PBIs reflect any and all business and development dependencies between the work tasks necessary to deliver them. Use Fixed-Date PBI for PBIs that depend on a particular calendar date (for example, because they are awaiting delivery of a previously ordered part with a promised delivery date).

While Scrum does not stipulate any format for PBIs, apply caution in relying on using user stories. User stories present a quick summary of some what for a PBI, but much of their value comes in identifying the stakeholder (who) and the stakeholder’s motivation (why). User stories are in the requirements space. One PBI may satisfy the requirements germane to several user stories. From the perspective of release management, the elements of the Product Backlog are deliverables awaiting development rather than the requirements that these deliverables satisfy. The team may use any format by which stakeholders can easily recognize or envision a deliverable to which they can relate.

PBIs that are smaller than about 10 percent of a Sprint delivery usually yield the best estimates. Get to Small Items with approaches such as Granularity Gradient to avoid the waste of breaking down the entire backlog. The Development Team should collectively estimate all PBIs (Pigs Estimate), with a best practice being Estimation Points.

The team should generally not use PBIs to direct inwardly focused work items or tasks: that confuses the value delivered with the mechanisms used to create that value. Such confusion can cause the business to lose its external market focus. PBIs tend to add value for the stakeholders, rather than to the work environment, manufacturing plant, or workspace. Use the Sprint Backlog for items like these if they support development of some PBI, and use the Impediment List to log process issues and to keep them visible.

The Development Team should manage its own work plan, or Sprint Backlog, without undue meddling from the Product Owner. Some items, like cleaning the shop floor, daily machine maintenance, or refactoring code, are so routine that they are not even explicit in the work plan let alone directed at the business level. Other internal-facing work items such as testing and writing purchase orders might be explicit in the work plan, but are unlikely to explicitly appear as PBIs. Sometimes, these items loom large enough to threaten long term value: for example, cumulative effects of ignoring daily machine maintenance, or Good Housekeeping, may leave a work environment that is unsafe or inefficient and which begs a sizeable cleanup effort. In these exceptional situations, the Product Owner may include bugs, overdue machine maintenance, technical debt reduction, and other traditionally inwardly facing items in PBIs because they have become large enough to merit business-level oversight.

On the other hand, while most PBIs relate to the Product Increment, a PBI can certainly describe any deliverable that increases stakeholder value. Advanced teams might use the concept of “stakeholder” in a broad sense. The team might even use PBIs for internal documents such as engineering diagrams because they add value for the team, which in this case we treat as a stakeholder; there will certainly be a PBI for any external user manuals. (An alternative is to treat internal documentation as part of the Definition of Done. As a rule of thumb, use PBIs for large units of internal work so they remain visible, and use the Definition of Done for small recurring units of work that would clutter the work plan.)

PBIs should nonetheless focus on what, when and for whom rather than how. If the Product Owner is spending much time dealing with the how of development rather than the what, when and who, then the team should seek out and address the underlying impediments. See also Illegitimus Non Interruptus for a description of an advanced approach for using PBIs to bring important concerns outside the Product Increment itself into sharp focus.

An advanced use of PBIs is to elicit process improvement work that requires work by the Developers during the Sprint. See Scrumming the Scrum.

When completed at the end of the Sprint, the product contribution driven by a Product Backlog Item must meet the Definition of Done.

You can order PBIs on the basis of cost and value aspirations (for what value means here, see Value and ROI). Even with all other things being equal, changing the position of a PBI in the backlog can change its contribution to value (e.g., because of market timing issues, such as a season or competitive dynamic). You can order the Product Backlog either on the basis of the individual value estimates for relatively independent PBIs (as in High Value First) or on the basis of overall, long-term, integrative ROI.

Picture credits: Shutterstock.com.