I once worked on a very large software project. Over time, our bug list grew larger and larger, until everyone realized that we had to do something. Management dispatched a team to clean up the bug list; to either fix the bugs or remove them from the list. A couple of months later, management announced with great fanfare that developers had reduced the bug list from around a thousand bugs to some six hundred, thus reducing the number of bugs from astronomical to merely unmanageable.

...the Development Team is in the throes of the Production Episode, adding new functionality to the code. You have, perhaps, committed to Good Housekeeping so you can sleep at night. As a Cross-Functional Team development, it feels like five steps forward and one step back: problems and emergent requirements interrupt progress and cause the team to lose focus. The team has a Definition of Done that encourages the team to leave no work undone, and to leave no known problem unresolved, at the end of the Sprint.

✥ ✥ ✥

There is always a tension between advancing product functionality and raising product quality.

Business pressures tend to make us view engineering problems, software bugs, and manufacturing line irregularities as necessary evils. We see them as distractions that lie outside the Sprint. And because developers really like to do new stuff, they often smooth over current product problems, or they postpone resolving them until the tomorrow that never comes. In software, such “small” issues often live under the radar of the tests that enforce Good Housekeeping. And even if one has the discipline to do Good Housekeeping comprehensively, one can’t afford to defer resolving issues until the end of the day: it’s hard to know how much time to set aside.

Fixing issues takes time, so we often defer such work. We believe that the market benefit is not worth the effort to fix them, or that they displace the “more important,” revenue-generating work. However, McConnell ([1]) has shown that bugs in software slow down the Development Team because they cause “stumbling“ and workarounds that create a drag on development. These impediments actually slow down other development that isn’t directly related to fixing bugs.

We could administratively define issue repair as “real work” to incentivize the Development Team to turn its energies to ongoing repair instead of focusing only on new things. However, developers in a healthy development context find intrinsic motivation to repair issues. And we want to avoid the administrative overhead of tracking issues: the tracking sometimes costs more than the repair itself.

Collecting all issues to a “cleanup Sprint” leaves the product in a broken state until that Sprint arrives. And even when completing such a Sprint, it doesn’t move the team along its Product Roadmap. It only makes it visible that the team members should feel guilty about where they believe they stand on the Roadmap: previously delivered Product Backlog Items (PBI) were in fact not properly delivered.

There is some cost of switching context from PBI development to issue mitigation. However, when developers see an issue, they are motivated to fix it now while the issue is fresh in their mind, in touch within the context. The more the team postpones the change (until later in the day, or until a subsequent Sprint), the more expensive it becomes. Subsequent changes in the environment or in the product may make it challenging to reproduce the issue later.

Issues that the team doesn’t fix now tend to accumulate, or become forgotten or lost in a defect-tracking system. Some issues may become legacy components of the product as technical debt grows—maintainability suffers and quality drops. Keeping an inventory is bad enough: keeping an inventory of defect descriptions is very un-lean. And keeping an issue work backlog separate from the backlog of value-generating work items makes it impossible for the team to know the total ordering of all work (issue-repairing and new value-generating). This situation can lead to one of two extremes: either issue resolution becomes a second-class citizen or the team becomes a firefighting team.

Bob Martin relates a story of once fixing a spelling error in an application. However, many customers had built screen capture scripts that depended on the misspelled word. Management ordered him to “unfix” the misspelled word.

One of our clients found that they awoke one morning to 2000 Category 1 (highest priority) bugs in their bug-tracking system and decided to launch a quality Sprint to reduce that number by 60 percent. Incentivized by the corporate reward structure, the teams met their goal—by reclassifying about 60 percent of those bugs as Category 2 bugs.

Therefore:

Immediately resolve product problems, big and small, as they arise. Don’t pause to create and review a Product Backlog Item, but rather fix defects as they become evident. The team should hold it to be a higher priority to fix a broken product or a product that does the wrong thing than to enhance the product. After all, the presence of any issue means the team has not or cannot deliver some aspect of product value. What it held to be Done was not Done. If it’s not clear whether the problem should be fixed, then the lack of clarity is itself a problem worth redressing immediately.

It doesn’t matter whether the team introduced the problem in the current Sprint or in a previous Sprint: to the market, an issue is an issue. And it doesn’t matter whether the issue was found in development or in the field: an issue is still an issue. Ensure that you have a good reporting path for issues up and down the Value Stream to give immediate visibility to all issues.

Developers should drop what they are doing and address product issues when they come to the attention of the Development Team. Developers should start by spending an agreed maximum number of hours (e.g., four hours) on the issue. Work should normally start on the issue without any significant engagement with the Product Owner. The Development Team should use its own judgement about whether a particular anomaly is actually a defect, but the Product Owner is available as an oracle if there is any doubt. The involved developers should in any case make the effort visible to the rest of the team through information radiators and the Daily Scrum. It is also good practice to make the work visible on the Sprint Backlog; keep this administration lightweight, as with sticky notes on a wall (see Information Radiator).

If the Development Team cannot remove the cause of the issue in the agreed time box, the team escalates it to the Product Owner. The Product Owner quickly decides whether to continue work on the issue at the potential expense of failing to complete all remaining PBIs in the Sprint, or alternatively creates a PBI for the issue and puts it visibly on the Product Backlog. If the Sprint Goal is at stake, the team may go into Emergency Procedure.

✥ ✥ ✥

One or two team members start work on the issue so that the rest of the team can continue making progress on a product increment that will generate new value; this helps better manage overall risk. See Team per Task.

Good discipline in use of this pattern will enable Good Housekeeping at the end of the day, and will demonstrate how serious the team is about Good Housekeeping. The end result is a heightened focus on the integrity of the Product Increment. Also, this pattern has a close relationship to Definition of Done. A good Definition of Done will limit discussions about whether an issue is really an issue or not. The Scrum Team should continuously extend the definition to improve the immediacy of product repair during production. And it’s important that the fix itself meet the Definition of Done. Just as importantly, the fix should not be a temporary patch that contributes to long-term technical debt.

This approach means you can do away with much issue administration, including the management of dependencies related to issues or issue prioritization.

This pattern can’t retire existing technical debt. The team can slowly retire technical debt by refactoring, or the Product Owner can raise refactoring or redesign to the business level with Product Backlog Items. Software refactoring is a form of this pattern at the micro level.

If this pattern causes the Development Team to do nothing but fix issues during the Sprint—which means unendingly deferring PBI development—this points to a serious quality problem that should probably cause the Product Owner to escalate Emergency Procedure all the way to Abnormal Sprint Termination. It should also result in serious head-holding during the Sprint Retrospective. See Illegitimus Non Interruptus as a high-discipline interim measure. Illegitimus Non Interruptus also helps moderate the effort put into emergent issue repair during the Production Episode. It does this by giving the Product Owner the option to consciously and visibly defer the resolution of a given issue until a later Sprint.

There are two distinct steps: fixing the issue, and fixing the process. The Scrum Team can address process changes after a calming period that follows the flurries of Sprint activity. The team can deal with the issues itself rather directly: each problem gets a fix. However, the corresponding process changes must consider broader context and subtle issues of organization, history, culture, and so forth. Process changes usually require more deliberation and focus than the team can muster in the middle of a Sprint, and team members often require Product Owner intervention—something we want to minimize during the Sprint. Except in obvious cases, leave process changes to the Sprint Retrospective, with consideration for implementation in subsequent Sprints. One good process fix might avoid hundreds of subsequent product fixes.

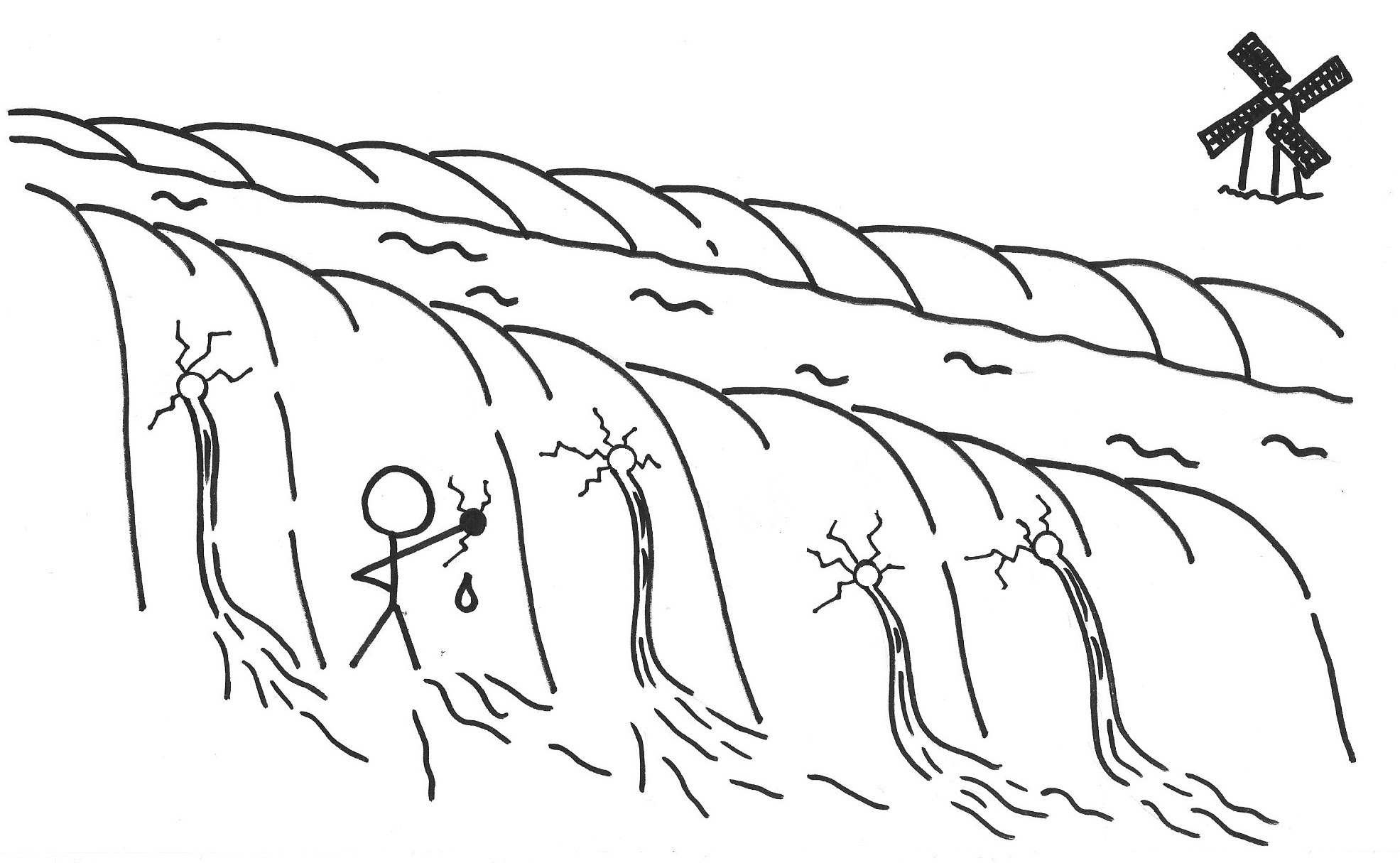

There are many supporting patterns that deal with competing priorities along the Value Stream. Daily Scrum orders the work items on this particular area of the Value Stream to give priority to plugging holes in the dike. Good Housekeeping ensures that the workspace itself doesn’t become flooded. Illegitimus Non Interruptus prevents the dike from ending up with so many holes that it collapses. Emergency Procedure flushes work in progress and redirects the flow.

See also Sacrifice One Person and Interrupts Unjam Blocking.

[1] Steve McConnell. “Software Quality at Top Speed.” In Software Development 4(8), August 1996, pp. 38–42.

Picture credits: Shutterstock.com.