...the Scrum Team is using Information Radiators to maintain transparency with all stakeholders.

✥ ✥ ✥

Without a frame of reference for your goals, you can unknowingly drift from them.

Our current goals strongly influence our behaviors, such as where we turn our attention (see [1] and [2]). Being focused on our work and direction actually dilutes our attention, as shown in a well-known video experiment where an observer is asked to count the number of ball passes between people, and totally misses someone in a gorilla suit walking through the scene; see [3].

Scrum provides both direction and opportunities to focus on our work, but doing so may inherently prevent us from observing important changes in our work or work products. For example, members of the Development Team may be so focused on their current Sprint Backlog Items so as to not notice an increase in defect rates—or equally the Product Owner may be so focused on the Product Backlog for the next Sprint that he or she misses important changes in sales results.

Although Scrum is a team sport, each person views the product and team’s status through their own frame of reference. Some developers may view everything as going well whereas others may see a crisis coming, but without consensus the team will not change how it approaches its work.

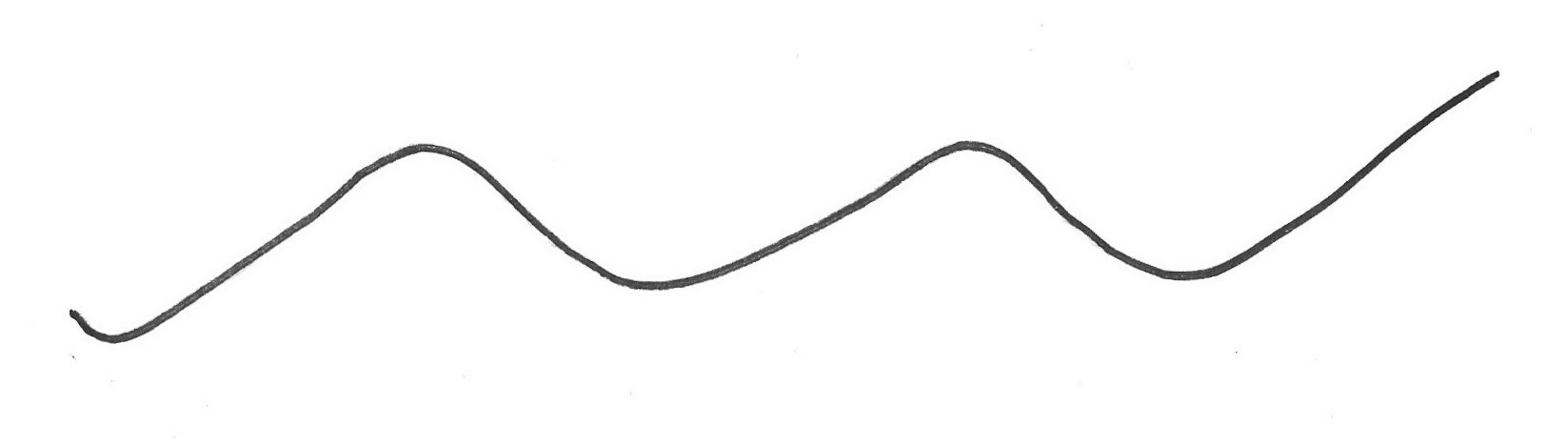

Using Information Radiators to maintain transparency is important for a functioning Scrum Team. Nonetheless, when the information does not create action, team members may passively accept whatever information that status boards and the environment provide. An example from our community: one of us was working with a company where at the end of the Daily Scrum, the Development Team members would look at the computer-generated Sprint Burndown Chart. No matter the shape of the burndown, the team did exactly what it had already agreed to during the Daily Scrum, even if the burndown was a straight, flat line. This is like a service message on the car dashboard that we ignore for months. This is different from the oil warning light that makes us stop the car straight away. We need both.

In spite of our best efforts at design and estimation at the beginning of a Sprint, we will be wrong. Finding out at the end of the Sprint that we were wrong does us no good.

Therefore:

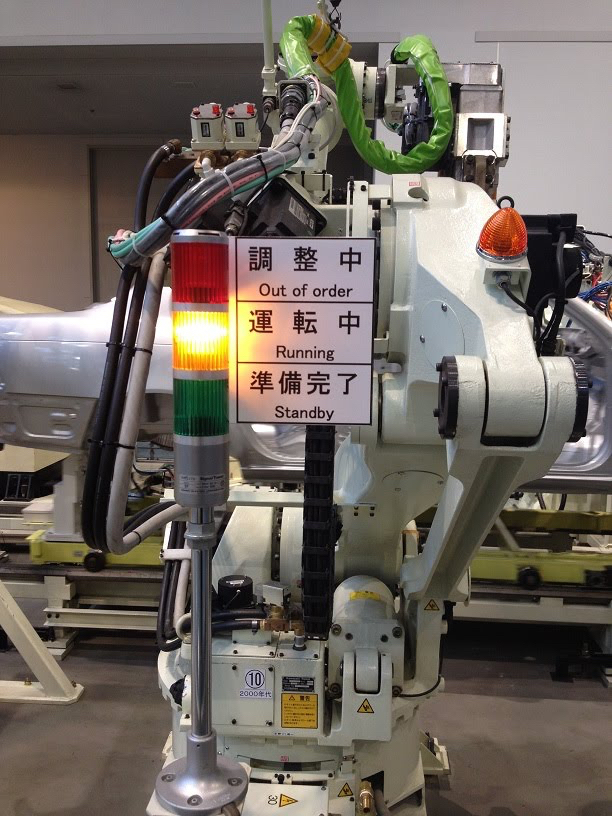

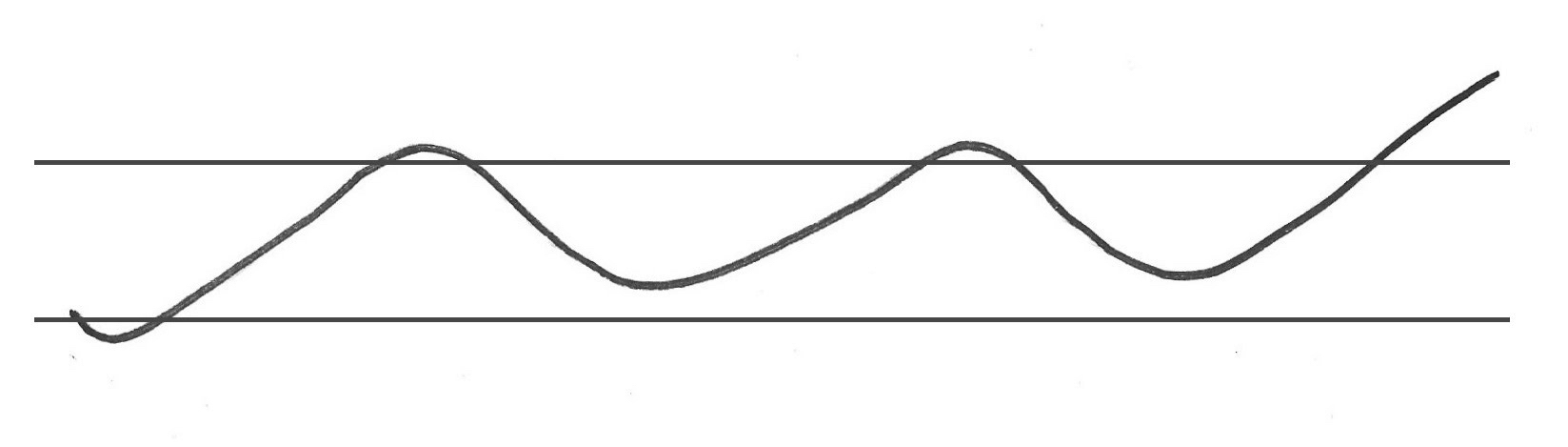

Create a status overview that demands action when outside acceptable tolerance. Information Radiators help to maintain the transparency for empirical process control but there is some information that cries out for immediate action. Use red lights, or emotive words like DANGER, or work environment lockouts on product and process state changes that need immediate attention and that disrupt the team’s anticipated work plan or sequence of actions. Get people's attention and let them know something is not in a normal state. It is necessary for the team to discuss what “normal state” means. When the team finds itself no longer using a particular Visible Status for improvements, the team members should agree to remove it.

The status indicator must make it easy and fast to grasp the meaning of the measurements. The indicator must communicate whether a given property of the process is within an acceptable range of tolerance (and requires no immediate action) or is outside the range. In the latter case, the team needs to know what measures to apply (by an explicit notice on the indicator or from prior training) to bring the process back within tolerance. Keep things simple and clear by showing only the most important information. Visual information is best as it is easy to continuously transmit it to many collocated people. To avoid unnecessary distractions, the Scrum Team should maintain the least number of status indicators as possible.

Posting status is all about transparency, information sharing, and motivation.

✥ ✥ ✥

If the team maintains Visible Status, it ensures that there are no surprises that come in the way of delivering a Regular Product Increment.

Use monitoring tools to gather data on all of the important metrics for your product and process and make them visible to the whole Scrum Team. Note that some metrics can be generated directly and automatically from the product or from related processes. There are many toolkits available for this, but you may also have to build something yourself. In either case, the final presentation to the team should be simple and obvious. Some examples out in the wild include:

- A traffic light to display whether the process is currently flowing smoothly.

- A lava lamp which signals that all is well when illuminated.

- A Homer Simpson statue that says “Mmmmm, donuts!” when a software engineer breaks the build, indicating that its now their turn to bring donuts for the whole team in the morning!

The call to action must be unambiguous. The change from no-action to action must also be clearly shared. This avoids losing time when the team is trying to make the decision, or worse, is not taking action because it is so used to ignoring the status.

Whatever you choose, it is important that the team clearly understand (from context, from a display on the status indicator itself, or from training) how much time it has to respond. For example, the traffic light could turn yellow if 24 hours is fast enough, or it could turn red when things need immediate attention. If high reliability is crucial to the business, the monitoring system may contact team members directly via their mobile phones (by analogy to Small Red Phone).

The action needed can also be predefined. For example, product defects require the team to Whack the Mole. Or, when the reality of the Sprint has drifted too far from the Sprint Backlog, the team executes Emergency Procedure. Use the Daily Scrum to replan and respond effectively as a team.

The Scrum Team needs to collaboratively develop the Visible Status. This will help to build greater understanding of the status indicators and the cross-functional work of the team.

Product health has many components, including the ongoing operations of the current system. There are many service-level indicators that developers may want to monitor continuously—CPU load, memory utilization, network utilization, application errors—far more than they can see at a glance. Google’s Site Reliability Engineer recommends alerting the team only when problems affect end users, and then making details available for easy drill-down for further investigation, as described in Chapter 6 of [4]. Note that monitoring ongoing operations of the deployed system itself is not part of Scrum.

How widely should the team share information from the Visible Status? There is no call to hide anything in Scrum. Use common sense: share as much as possible but don't bother everyone with something that affects people only locally. If you walk the gemba (factory floor) and see an indicator that is active, then find out if you can be of any assistance. Reflect carefully if you feel this pattern facilitates comparing indicators between teams, and you become tempted to use the information to identify “the better team.” If you do conclude you should compare teams, please reflect again.

Of course, make sure that you collect and display only accurate and relevant status data.

When the Development Team members can access accurate, up-to-date data, they get a better idea of where they are. They are in a position to make in-course corrections during a Sprint to help them achieve the Sprint Goal. They often do this of themselves, with little or no overt prodding from the ScrumMaster.

This pattern has origins in the Toyota Production System (TPS). TPS has Information Radiators, such as a large overhead board that tracks production measures in the factory. These are the system metrics. But more importantly, the TPS factory floor also uses indicators that flag the need for immediate attention. An engineer can signal that a defect has arisen in a product or in the process by pulling a clothesline-like cord called the andon cord (literally, “lamp cord”). This sets a small flashing lamp into action and initiates background music to draw attention to the problem. The Chief Engineer and others may come to help resolve the problem; they resolve most problems in seconds, and the lamp turns off and the music stops. If the car starts to cross the line into the next work cell, it activates a more global factory indicator and the line stops because the defect now threatens the production of that car and the entire line. It is a signal that begs immediate human intervention. The idea in turn took inspiration from an invention by Sakichi Toyoda, who ran the loom manufacturing company from which Toyota Motor Corporation would spring. His invention caused a loom to shut down and ring a bell when it detected that either the warp or weft thread had broken so a person could intervene, fix the problem, and set the machine back into motion. He sold the invention to the British for £300,000, and with the money, started the Toyota Motor Corporation.

Isao Endo states in his book about mieruka (visualization) that there is a need to make people aware of situations and change their behaviors and actions. Mieruka also must show how the situation changes after people take action, as Endo writes in [5]. He believes that mieruka is the core concept of gemba power.

[1] Don VandeWalle and Larry L. Cummings. “A test of the influence of goal orientation on the feedback-seeking process.” In Journal of Applied Psychology 82(3), 1997, pp. 390–400.

[2] Edwin A. Locke and Gary P. Latham. “Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey.” In American Psychologist 57(9), 2002, pp. 705–17.

[3] Daniel J. Simons and Christopher F. Chabris. “Gorillas in Our Midst: Sustained Inattentional Blindness for Dynamic Events.” In Perception 28(9), Sept. 1999.

[4] Niall Murphy, Betsy Beyer, Chris Jones, and Jennifer Petoff. “Sharding the Monitoring Hierarchy.” In Site Reliability Engineering: How Google Runs Production Systems. Sebastopol, California: O’Reilly Media, April 2016, Chapter 6.

[5] Isao Endo. Mieruka. Tokyo: Toyo-Keizai-Shinbun-Sha, 2005.

Picture credits: The Scrum Patterns Group (James Coplien).